The Fastest Men of the Century in the 100 meters of the Olympic Games | Second Part (1948-1996)!

Second Part (after World War II)

1948-1996!

From Harrison Dillard to Donovan Bailey….

1948 London

W. Harrison Dillard (USA) 10.3 EOR

Harrison Dillard was a 13-year-old schoolboy in Cleveland when he attended the huge parade in 1936 in honor of Jesse Owens. Later he met Owens, who took a liking to the young man and presented him with his first pair of running shoes. Dillard put those shoes to good use.

W. Harrison Dillard (USA) 10.3 EOR

By 1952 he had matched his hero’s total of four Olympic victories. From May 31, 1947, through June 26, 1948, “Bones” Dillard, running mostly the hurdles, ran up an unprecedented string of 82 consecutive victories.

The streak finally came to an end at the A.A.U. meet in Milwaukee when he tried to run four races in 67 minutes. First he lost the 100 meters to Barney Ewell and then he lost the 110-meter hurdles to Bill Porter.

Nevertheless, when the Olympic trials were held the following week in Evanston, Illinois, there seemed no surer gold medal bet than Harrison Dillard, the world record holder in the 110 meters hurdles.

However, in the final he uncharacteristically hit the first hurdle, lost his stride, hit two more hurdles, and stopped at the seventh hurdle as the others raced ahead. Dillard’s Olympic hopes seemed over. Fortunately he had qualified the day before as third man in the 100 meters. But Dillard would face stiff competition in London. First there was the prerace favorite, U.S.C.’s Mel Patton, who held the world record of 9.3 in the 100 yards.

Then there was 30-year- old Barney Ewell, who had beaten Patton at the U.S. trials in the world record time of 10.2. And there was Patton’s arch rival, Lloyd LaBeach of U.C.L.A., who had also run 100 meters in 10.2 and who went to London as the sole representative of his native country, Panama.

The three favorites and Dillard were joined in the Olympic final by two representatives of Great Britain, Mac Bailey of Trinidad, who, like Dillard, had been inspired by the feats of Jesse Owens, and Alastair McCorquodale, a burly Scot who had taken up running only a year earlier and who actually preferred rugby and cricket to track.

After one false start, Dillard flashed into the lead and held it the entire way. Ewell caught him at the tape and, thinking he had won, danced around the field joyfully and embraced his opponents. But LaBeach told him, “Man, you no win; Bones win.” LaBeach was right. When the photo-finish had been studied, it was announced that Dillard had won. Ewell graciously congratulated him on his good fortune, greatly impressing the crowd of 82,000 with his sportsmanship. LaBeach, whose parents were Jamaican, is the only Panamanian ever to have won an Olympic medal.

1952 Helsinki

Lindy Remigino (USA) 10.4

The 1952 100-meter final produced one of the closest finishes in Olympic history and also one of the biggest sprint upsets. The title seemed pretty much up for grabs, particularly after the U.S. college champion, Jim Golliday, was injured and unable to participate in the Olympics.

Lindy Remigino (USA) 10.4

The position of favorite shifted to 31-year-old Mac Bailey and Arthur Bragg of Morgan State College. But Bragg pulled a muscle in the semifinals, which were won by Bailey and 30-year-old Herb McKenley, the 400-meter world record holder who had also entered the 100 as a means of practicing his start. With this race McKenley became the first-and only-man to qualify for a final in the 100 meters, 200 meters, and 400 meters.

One of the surviving U.S. representatives was Texan Dean Smith, who also competed in rodeos and who later became a stuntman in hundreds of television shows and films, including Stagecoach and True Grit, and doubled for Robert Redford three times in the early 1970s.

The other was Lindy Remigino, a modest Manhattan College student from Hartford, Connecticut. Remigino must have been amazed to find himself a finalist in the Olympics. He had barely quali- fied for the U.S. Olympic tryouts by finishing fifth in the N.C.A.A. championship.

Smith showed in front first, but Remigino had a clear lead at the halfway mark. He held on gamely for 90 meters, but was passed by McKenley just as they reached the tape.

“I was sure I had lost the race,” said Remigino after- ward. “I started my lean too early and I saw Herb McKenley shoot past me. I was heartsick. I figured I had blown it.” Lindy walked over to the delighted Jamaican and offered his congratulations.

The controversial finish of 1952 100 meters dash…

But a photo-finish showed that Remigino’s right shoulder had reached the finish line an inch ahead of McKenley’s chest, and the judges ruled him the winner. When someone told Remigino the results before they had been flashed on the scoreboard, he was incredulous and was sure there had been a mistake.

Finally he turned to McKenley and is reputed to have said, “Gosh, Herb, it looks as though I won the darn thing.” The close- ness of the finish is shown by the fact that Dean Smith was only 14 inches behind the winner, yet placed only fourth.

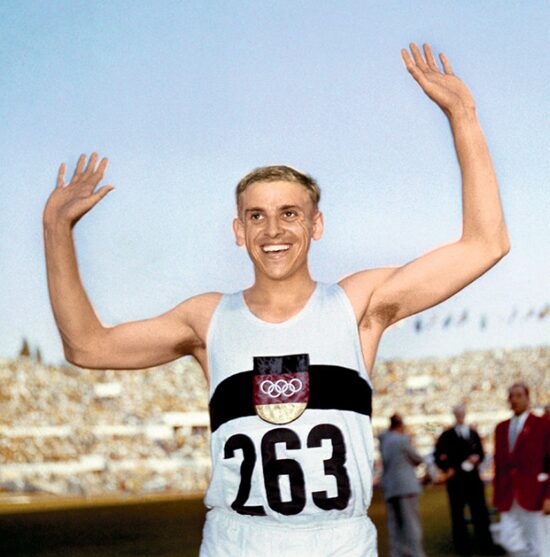

1956 Melbourne

Bobby Joe Morrow (USA) 10.5

The Olympic record was tied in the second round by the favorites, 6-foot 1/21⁄2-inch Bobby Morrow and 5-foot 4%1⁄2-inch Ira Murchison. The same pair won the two semifinal heats with Morrow again running 10.3. The final was run into a nine-m.p.h. wind, which accounts for the slow times.

Bobby Joe Morrow (USA) 10.5

Hec Hogan, the five-time Australian 100-yard champion from Queensland, took the early lead, but Morrow passed him after 50 meters and stormed to a decisive victory.

Baker and Murchison caught Hogan with 25 yards to go, but Hogan churned out a final burst, and only a desperate lunge by Baker kept the Aussie from a silver medal. Morrow, a devout Christian from San Benito, Texas, never tried to anticipate the starters’ gun with a rolling start because he considered it unsportsmanlike.

A cotton and grain farmer, he relied on get- ting 11 hours’ sleep a night to keep up his strength. “Whatever success I have had,” he said, “is due to being so perfectly relaxed that I can feel my jaw muscles wiggle.” Bronze medalist Hogan died of leukemia at the age of 29 on September 2, 1960, the day after the 100-meter final at Rome.

1960 Rome

Armin Hary (GER) 10.2 OR

On June 21, 1960, controversial Armin Hary, an office worker from Frankfurt, became the first man to be credited with 10.0 in the 100 meters. Running in Zurich, this fast-starting son of a coal miner in Quierschied, Saarland, actually achieved the time twice in one day.

On the first occasion he was accused of “taking a flyer,” or beating the gun, a tactic for which he was notorious. When the starter ordered the race rerun, Hary protested, but went ahead and ran another 10.0.

Three and a half weeks later, on July 15, the son of a Pullman coach attendant, 19-year-old Harry Jerome of Vancouver, recorded the second official 10.0 at the Canadian Olympic trials at Saskatoon.

Despite the achievements of Hary and Jerome, most track aficionados were predicting victory for Ray Norton, who had swept both sprints at the U.S.A-U.S.S.R. meet, the 1959 Pan American Games, and the 1960 U.S. Olympic trials. Another contender was Dave Sime, a medical student from Fair Lawn, New Jersey. Sime set a rather unusual world record when he ran 100 yards in 9.8 seconds while dressed in a baseball uniform. The previous record had been set by Jesse Owens in 1936.

Armin Hary (GER) 10.2 OR

In the second round in Rome, Armin Hary beat Dave Sime by a yard and set an Olympic record of 10.2. The first semifinal was won by Peter Radford, a Walsall schoolteacher who had spent three childhood years in a wheelchair because of a kidney disease. Harry Jerome had been in the lead when he pulled a muscle and couldn’t finish. The second semi saw Armin Hary beat both Sime and Norton, who was running unusually tightly.

The start of the final was a tense affair. First Hary and Sime broke without a gun, but neither was penalized. The next try for a start was halted when Figuerola needed his starting block repaired. Then Hary beat the gun and was penalized.

One more false start and he would be disqualified. But the usually volatile Hary kept his poise and at the next attempt got off to a fair and perfect start. By the end of the first stride he was already in the lead, and at the five-meter mark he led by a full meter.

In the second half of the race, Sime stormed back from last place to make up over three meters, but Hary held on to win by a “long foot.” Not only was Armin Hary the first winner of the Olympic 100 meters to come from a non- English-speaking country, he was also the first German male to win an Olympic gold medal in a track event.

In the end Hary proved that his amazing “blitz start” was legitimate. He contended, however, that there was more to it than quick reflexes.

“More.important to me,” he said, “is the fact that I have learned, through relaxation, how to achieve full stride and smooth forward action very early in the race.”

He did, however, employ one “trick.” Whenever the starter called “set,” Hary would stay down until all the other runners were hanging heavily in the set position.

Only then would he rise. Unsuspecting starters would invariably wait for him and then pull the trigger for the start, allowing Hary, in effect, to control the beginning of the race.

Knowing that the anxious starter would pull the trigger as soon as he was set, Hary would rise, pause a moment, and then take off just as the gun was sounding.

Hary’s competitive career came to an abrupt halt shortly after the Olympics, when his knee was severely. injured in an auto accident. In 1981 his name reappeared in the news when he was convicted of diverting Roman Catholic Church funds for use in a personal investment.

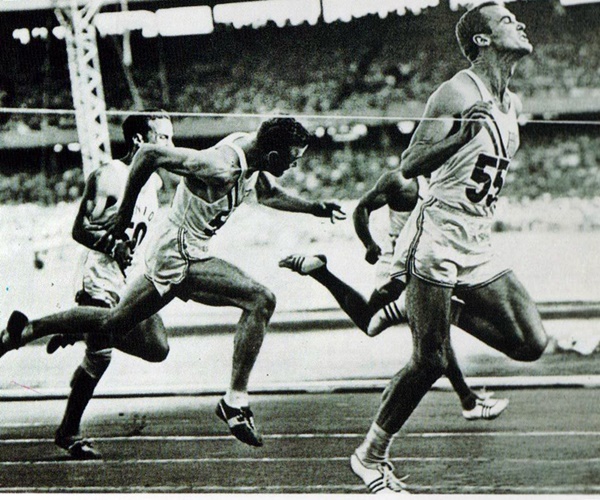

1964 Tokyo

Robert Hayes(USA) 10.0

This was one 100-meter final that was run exactly to form. Any doubts that Hayes had not recovered from a June leg injury were quickly dispelled when the burly, pigeon-toed Florida speedster demolished the field in the first semifinal in a wind-aided 9.9.

Robert Hayes(USA) 10.0

Harry Jerome won the second semi, ahead of Kone, Figuerola, and Pender. Pender led most of the way but tore a rib muscle and had to be carried off the field on a stretcher.

Advised by doctors to withdraw from the final, he ran anyway and spent the next three days in the hospital as a result. Hayes, who was the first person to run 100 yards in 9.1 and the first person to break 6.0 for 60 yards, entered the Olympics with a record of 48 straight finals victories at 100 yards and 100 meters.

The start was delayed 10 minutes while the curb lane, Hayes’ lane, was raked after having been chewed up by the start of the 20-kilometer walk. The big three, Hayes, Figuerola, and Jerome, had pulled away from the others by the 10-meter mark. Then Hayes unleashed his power, took a one-meter lead halfway, and pulled away to an awesome seven-foot victory.

Both Figuerola, who became the first Cuban to win an Olympic track and field medal, and Jerome called it the best race they had run all year and had nothing but praise for the winner. After the Olympics, Bob Hayes became the first Olympic champion to make a successful transition to professional football.

He played nine years for the Dallas Cowboys and was twice chosen All-Pro as a wide receiver. Hayes was so fast that opposing teams had to abandon their traditional man-to-man pass defenses and create the zone defenses that are the standard today. When he retired from football, Hayes plunged into alcoholism and drug use. In 1978 he was arrested by undercover narcotics agents and the following year he pleaded guilty to selling cocaine and methaqualone.

In 15 he went from the top of the Olympic podium to a cell year in a Texas prison. He served ten months, drifted back to alcohol and drugs, and then underwent successful rehabilitation. In 1994, at the age of 51, Bob Hayes earned a degree in elementary education from Florida A&M University.

1968 Mexico City

James Hines (USA) 9.95 WR

The first accredited time of 9.9 seconds for 100 meters was registered at the A.A.U. championships in Sacramento, California, on June 20, 1968, by Jim Hines, the son of an Oakland construction worker.

Hines had run a wind-aided 9.8 in a heat, then followed with his history-making run in the semi- final. However, in the final he was beaten by Charlie Greene, a graduate of the University of Nebraska. Previous to the Olympics, Hines and Greene had met in 12 finals, with Greene winning eight of them. However two of Hines’ four victories had been the last two times they met, at the U.S. Olympic trials.

Competition was stiff in Mexico City. In the second round Heinz Erbstösser of East Germany had the distinction of being the first person to run 10.2 and not qualify for the semifinals. Greene clocked 10.0 in his first two heats, while Hines matched the time in the semis.

Hermes Ramirez of Cuba also ran 10.0 in the second round, but was eliminated in the semis. The 1968 100 meters saw the first all-black final in Olympic history. Hines got off to what he later said was the best start of his career. However it was U.S. Army captain Mel Pender, now 30, who took the early lead. By 50 meters Hines and Greene had pulled even, and at 70 meters Hines shifted gears and pulled away to win by a meter. Greene, discouraged and suffering a cramp, was nipped at the tape by Lennox Miller, who represented U.S.C. in U.S. collegiate competition.

Hines’ electronically timed 9.95 was considered faster than the hand-timed world record of 9.9. Four days after his Olympic victory, Hines signed a contract with the Miami Dolphins football team. Another man who went into professional sports was Japan’s Hideo Iijima, who made it to the semifinals in 1964 and 1968. As the fastest sprinter in Japanese history, Lijima attracted the attention of the Lotte Orions baseball team, who hired him to become a pinch-runner and base-stealer. The club insured Iijima’s legs for 50 million yen. Unfortunately Iijima, though fast, hadn’t played baseball since he was 12 and had no aptitude for getting a jump on a pitch or for slid- ing. After two years, during which he was caught stealing 17 of 40 times, he was finally dropped from the team.

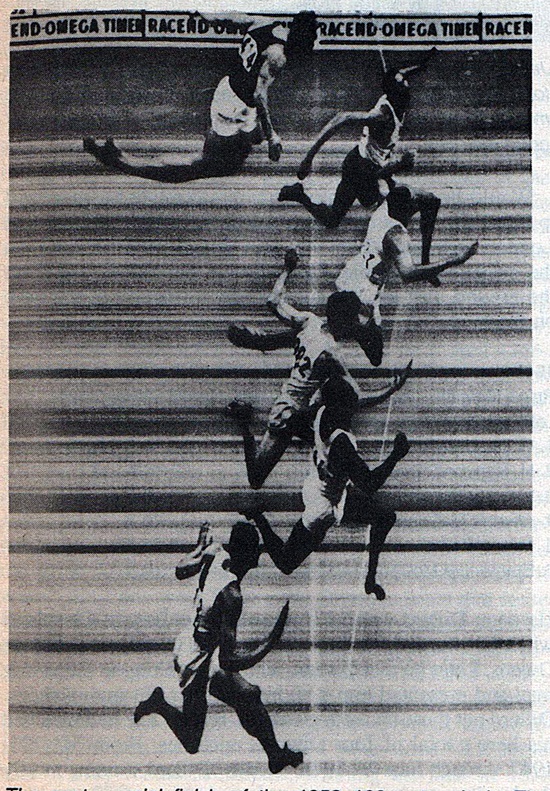

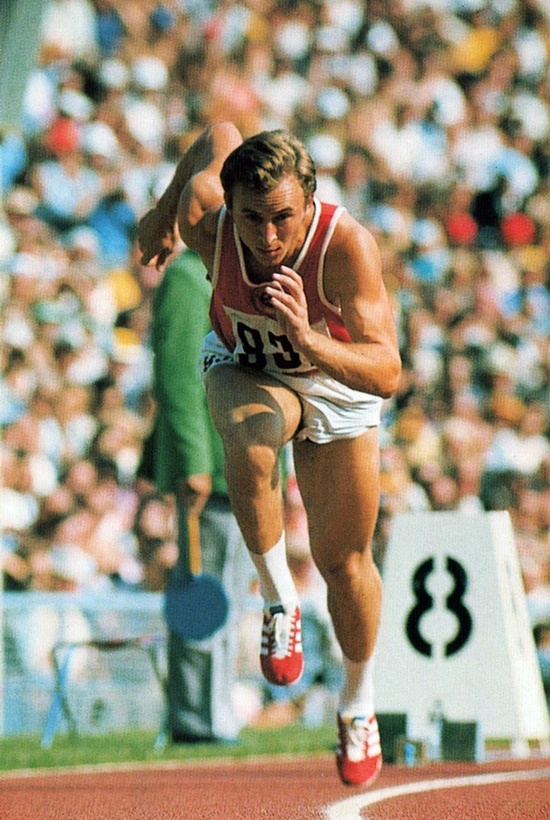

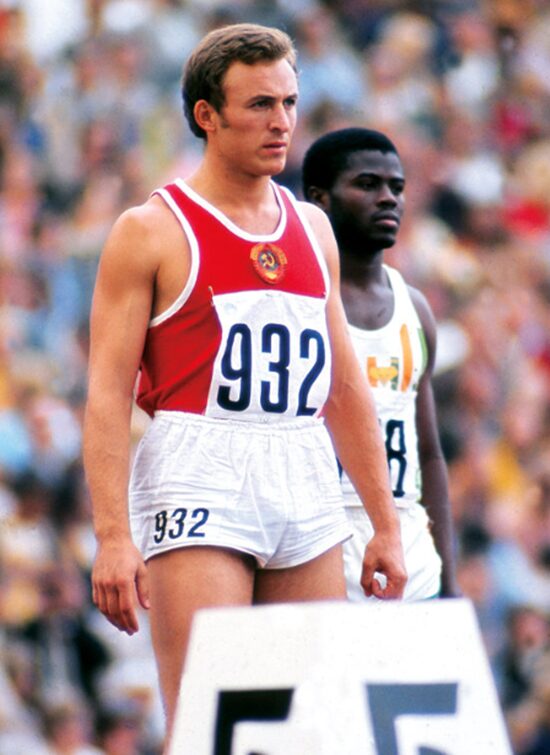

1972 Munich

Valery Borzov (SOV/UKR)10.14

Valery Borzov was the clear favorite in 1972. The blond, blue-eyed Ukrainian from Sambir was extremely consistent and had not been beaten in almost two years.

Valery Borzov (SOV/UKR)10.14

However, Eddie Hart of Pittsburg, California, and Rey Robinson of Lakeland, Florida, had both been timed at 9.9 in the U.S. Olympic trials. Hart was considered the number-one threat to Borzov.

The first round of 12 heats began at 11:09 a.m. on t31. Borzov, Hart, and Robinson each won their heats. August 3 Vassilios Papageorgopoulous of Greece recorded the fastest time of the round, 10.24, a time that might have earned him a silver medal had he not suffered a groin injury that forced him to withdraw from the semifinals.

The second round, the quarterfinals, was scheduled to commence at 4:15 p.m. As that time drew nearer, 1968 400-meter gold medalist Lee Evans noticed that Hart, Robinson, and the third U.S. sprinter, Robert Taylor, had not yet arrived at the stadium.

When he couldn’t find them at the warm-up track, Evans began to worry. Scheduled to run in the 4 x 400-meter relay later in the week, he raced at top speed from the stadium to the Olympic Village three quarters of a mile away in search of the missing Americans. But it was too late.

Two minutes earlier, Hart, Robinson, and Taylor, thinking the quarterfinals didn’t begin until 7 p.m., had casually left their quarters to return to the stadium.

Accompanied by their coach, Stan Wright, who had been working from an outdated 18-month-old preliminary schedule, the trio made their way to the bus stop at the Village gate. While waiting for the track stadium bus, they wandered into the doorway of the ABC-TV headquarters and began watching the television monitor.

What they saw on the screen was several 100-meter runners lining up at the starting line. Robinson asked if this was a rerun of the first round. Told that it was a live transmission, Robinson realized with horror that he was watching the very heat in which the had been scheduled to run. Hart was entered in the second heat and Taylor in the third.

The three athletes and their coach were pushed into a car and driven at breakneck speed to the stadium by ABC employee Bill Norris. It was too late for Robinson and Hart, but Taylor, who, like Jim Hines, had studied at Texas Southern, arrived just in time to slip off his sweats, put on his shoes, do a couple knee bends, and settle into the Starting blocks.

He finished second in the heat, a yard behind Borzov, which is exactly where he ended up 25 hours later, in the final. In that race, Borzov took the lead after 30 meters and was never headed. He even eased up at the end, throwing his as wide in exultation five meters from the finish. A last- chance dive gained dental student Lennox Miller third place aver Aleksandr Kornelyuk, the 5-foot 5-inch surprise from Azerbaijan.

Oddly enough, Borzov almost missed the same quarter- final heat that Hart and Robinson missed. First he was misinformed about the starting time of his heat. His coach convinced him to stay in the stadium. Borzov dozed off, and when he awoke his heat was being called. He raced to the track, but was stopped by a German official. Pushing aside the official, Borzov got to the line just in time to pre- pare his starting blocks.

Following the final, Borzov told reporters (in English) that he owed his success, “First and foremost to my country, secondly to my coach, Valentin Petrovsky, thirdly to all the people who helped me develop, and fourthly, to myself.”

Borzov wasn’t just toeing the party line. Listen to Petrovsky explain what went on at the Kiev Institute of Physical Culture, where Borzov was a graduate student: We began with a search for the most up-to-date model of sprinting. We studied slow-motion films of leading world sprinters of past and present, figured out the push-off angle and the body incline at the breakaway and went deeply into a whole number of minor details. . . .

For Borzov to The able to clock ten seconds fiat over 100 meters, a whole team of scientists conducted research resembling the work of, say, car or aircraft designers…. When the mathematical equivalent of a runner was worked out and given a scientific basis, we began testing our calculations in practice.

“I was subtle work, which could be compared to the training of a ballerina”.

Such statements give the impression that Borzov was just a machine, but he was quite human. He once said, “I very often have the following urge: I suddenly feel on the street that I have to run. I absolutely have to run, dressed in a suit, wearing my hat and tie, not paying any attention to the passers-by. . . . Then convention gets the upper hand and I restrain myself.”

Borzov eventually married the famous gymnast Lyudmila Turischeva, who won even more gold medals than he did.

He later served as President of the Ukrainian Olympic Committee and a member of the International Olympic Committee.

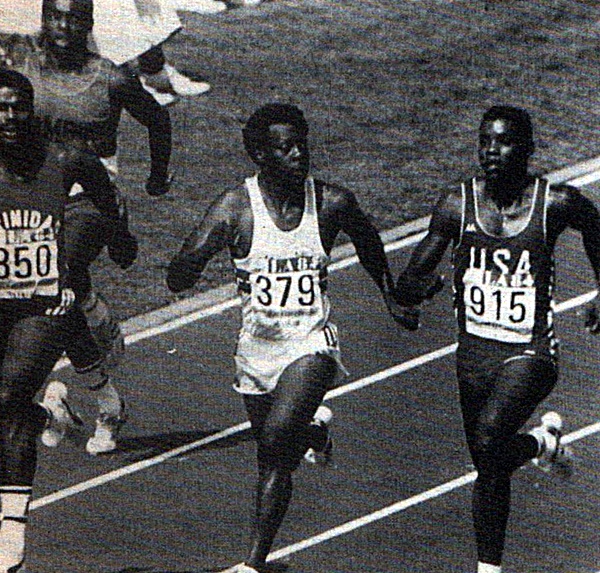

1976 Montreal

Hasely Crawford (TRI) 10.26

Several runners were given a strong chance to win, but the leading choices of track experts were Donald Quarrie, Silvio Leonard of Cienfuegos, Cuba, and Valery Borzov, who was aiming to become the first man to win two 100- meters gold medals (not counting Archie Hahn, whose second victory was in the Intercalated Games of 1906).

Hasely Crawford (TRI) 10.26

In fact, Borzov was the first gold medalist even to attempt the feat since Percy Williams had been eliminated in the semifinals in 1932. The first of the leading contenders to fall by the wayside was the accident-prone Cuban Silvio Leonard.

Leonard had won the 100 meters at the 1975 Pan American Games in Mexico City, but had pulled a muscle as he crossed the finish line. Hobbling forward in pain, he was unable to stop himself and fell into the ten-foot moat that surrounded the track. Seriously injured, Leonard nonetheless regained his form in time for the Olympics. Ten days before the Games, however, he stepped on a cologne bottle during a bit of horseplay and cut his foot. He was eliminated in the quarterfinals.

Meanwhile, 6-foot 24-inch Hasely Crawford, a gear machinist from San Fernando, Trinidad, was breezing through his heats. In the quarterfinals he beat Borzov, and in the semis he defeated Quarrie. Crawford had been a finalist in Munich four years earlier but had stopped running after four or five strides, the victim of a hamstring pull and nervousness. He was still fighting his nerves in Montreal, but he wasn’t the only one.

In the staging room before the final Crawford ranted and raved and tried to intimidate his opponents. When he stared at Glance and Jones, who were only 19 and 18, respectively, their “eyes showed they were already defeated.” Crawford later told reporters, “At the line I knew I could beat Borzov. I feared Don Quarrie.”

At the starting line, Crawford “shook a little bit,” but got a good start anyway. Glance took the early lead. Quarrie caught him after 60 meters and passed him at 75 meters. Then Crawford flew past on the curb lane. He stumbled just before the finish, but held off the lunging Quarrie to win. Crawford kept running for another 150 meters, then stopped suddenly, as if the realization of his accomplishment had just hit him.

As Trinidad’s first Olympic champion, Crawford received more than his share of honors. He was awarded the Trinity Cross, his picture appeared on two postage stamps, an airplane was named after him, and six different Calypso songs were written in his honor.

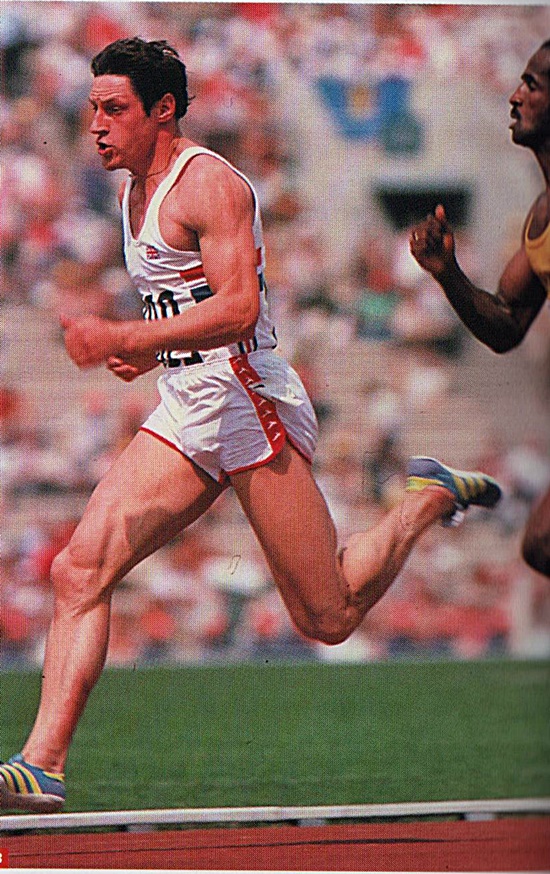

1980 Moscow

Allan Wells (GBR) 10.25

Stanley Floyd of Albany, Georgia, won the U.S. Olympic trials and also recorded the best time of the year (10.07). But with U.S. athletes boycotted out of the Olympics the mantle of favorite fell to Silvio Leonard, who had successfully managed to steer clear of moats and cologne bottles. His most serious challengers were considered to be Marian Woronin, who predicted that he would win the gold medal in a time of 10.10, and Eugen Ray of East Germany.

Allan Wells (GBR) 10.25

Aleksandr Aksinin recorded the fastest time of the first round-10.26. When the draw was announced for the second round, many eyebrows were raised. Of the nine first-round winners, four were thrown into the first heat, as was defending champion Hasely Crawford.

On the other hand, heat number three saw Aksinin unburdened by com- petition from other first-round winners. Aksinin won that heat in 10.29, a time that would have placed him seventh in the first heat. Heat number one was won by Allan Wells, a marine engineer from Edinburgh who didn’t start train- ing fulltime until six months before the Olympics. His time of 10.11 pushed him to cofavorite with Leonard.

The final took place during the last round of the triple jump, an event of great interest to the Soviet crowd. Just as the starter called “set,” a great roar went up for a jump made by local favorite Viktor Saneyev.

The starter held the runners in their crouch, then shot the gun. Aksinin and Lara were off the fastest, with Leonard and Wells close behind. By 60 meters Lara had faded, and by 80 meters the race was between Leonard on the inside and Wells on the out- side. Wells edged ahead, but Leonard drew even again.

With seven meters to go, the stocky Scot began an extreme lean that allowed his shoulder to cross the finish line two or three inches before Leonard’s chest. Allan Wells had become Great Britain’s first 100-meters winner since Harold Abrahams and Scotland’s first track gold medalist since Eric Liddell. At 28 he was also the oldest winner of the 100 meters at that time. As a youngster Wells had enrolled in a Charles Atlas correspondence course in body- building. His father was a blacksmith and his mother sewed nets for fishermen and worked as a hospital cleaner.

Wells didn’t turn from long-jumping to sprinting until 1976, at which time his personal best was only 10.9. Coached by his wife, Wells did not use starting blocks until 1980, when the International Amateur Athletic Federation (I.A.A.F.) required their use in international competitions. In addition to being an Olympic champion, Wells gained a place in his- tory as the first sprinter to wear thigh length cycling shorts.

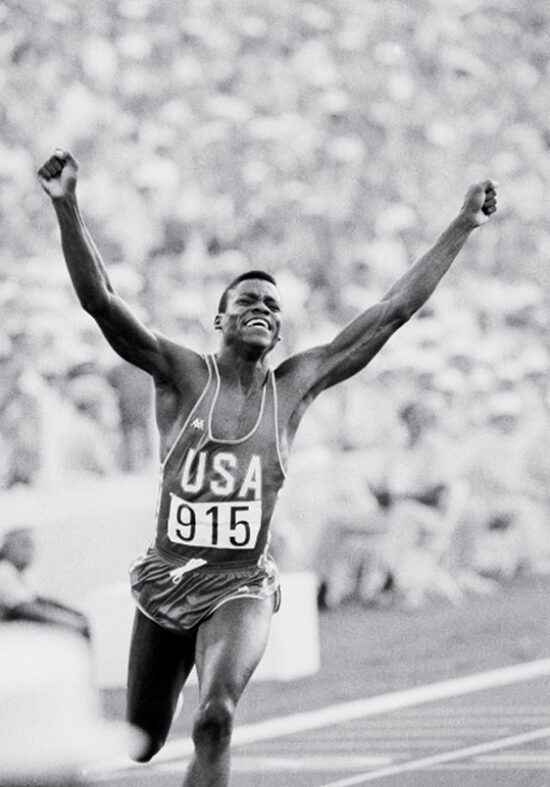

1984 Los Angeles

F. Carlton Lewis (USA) 9.99

The third son of two track coaches, Carl Lewis was born in Birmingham, Alabama, and raised in Willingboro, New Jersey. Small for his age and shy, Lewis began to grow so rapidly at the age of 15 (two and a half inches in one month), that he had to walk with crutches for three weeks while his body adjusted. Previously thought to be the least athletic member of his talented family, Lewis’ achievements began to outstrip all around him.

F. Carlton Lewis (USA) 9.99

By 1981 he was ranked number one in the world in the 100-meter dash and in the long jump. In June of 1983, he won the 100, the 200, and the long jump at the U.S. national championships, the first person to do so since Malcolm Ford in 1886. Two months later, he earned three gold medals at the Helsinki world championships. The following year he qualified for four events at the Los Angeles Olympics, giving him the opportunity to match Jesse Owens four-gold-medal feat of 1936.

Lewis’ first stop was the 100 meters, the event at which he was considered most vulnerable. As it turned out, he dominated the field. His second-round time of 10.04 was the best ever at a low-altitude Olympics. In the final, Graddy and Johnson were out fastest. Graddy still led at the 80-meter mark. “I thought, ‘Hey, I’m going to win a gold medal,”

Graddy would later say. “Then I saw him out of the corner of my eye.” Lewis, who was clocked at 28 m.p.h. at the finish, pulled away so strongly that his winning margin was a remarkable eight feet-the widest in Olympic history. Carl Lewis had won the first of his four gold medals.

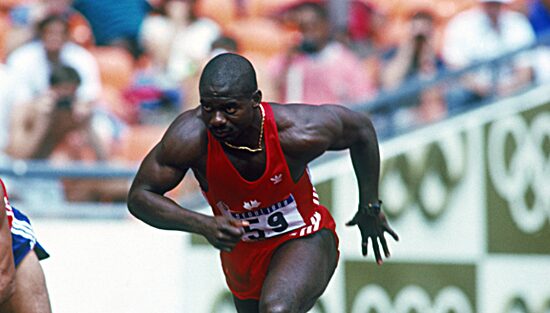

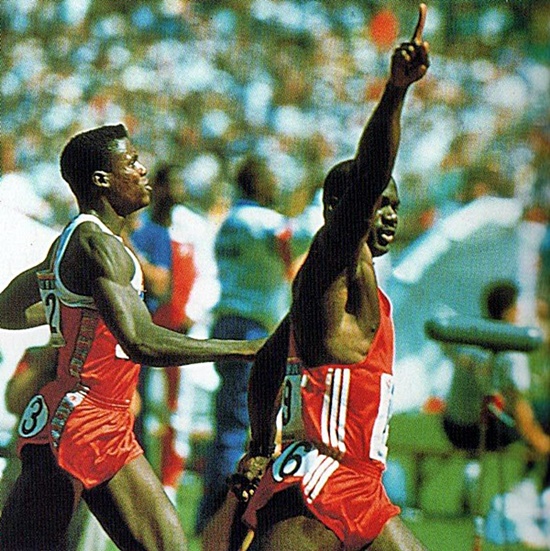

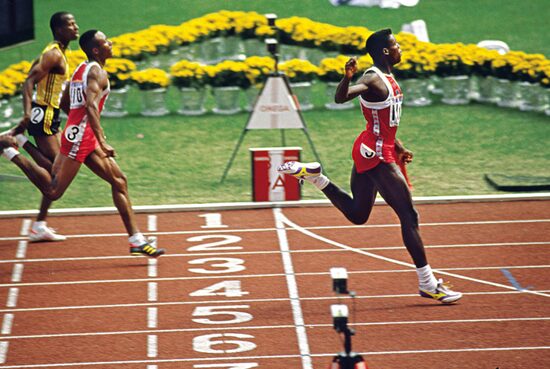

1988 Seoul

F. Carlton Lewis (USA) 9.92 OR

DISQ (Drugs): Benjamin Johnson (CAN) 9.79

Ben Johnson was born in Falmouth, Jamaica, on December 30, 1961. Small and shy, he began to stutter at the age of 12 as a result of constantly mimicking his older brother’s stammer. When he was 14 he moved to Toronto with his mother and three of his five siblings. Like his future rival, Carl Lewis, Johnson experienced a rapid growth spurt when he was 15 years old. It was also at this time that Johnson came under the tutelage of sprint coach Charlie Francis, the man who would guide his running career for the next 11 years.

On August 29, 1980, Johnson took part in the Pan American Junior Championships in Sudbury, Ontario, finishing sixth with a time of 10.86. This seemingly unimportant race would, in retrospect, earn significance as the first encounter between Johnson and Lewis, who won the contest in 10.43. Johnson scored his first major international success two years later when he finished second at the 1982 Commonwealth Games.

Two years after that he qualified for the 100-meter final at the Los Angeles Olympics. After purposely false-starting in an unsuccessful fill attempt to rattle Lewis, Johnson surprised track fans by earning the bronze medal behind Lewis and Sam Graddy.

In 1985, after seven consecutive losses, Johnson finally defeated Lewis. By 1986 there was no question that “Big Ben” had wrested the title of Fastest Man on Earth from “King Carl.” By the time of their classic confrontation at the 1987 world championships in Rome, it was Johnson who had won their last four encounters. By that time, also, Johnson had developed a reputation as an incredibly fast starter who appeared to leap out of the blocks like a panther going after a kill or a guard dog attacking an intruder.

In the Rome final he burst off the line with so much power that he almost fell over. After ten meters he was already in front by a full meter, a lead he would hold all the way to the finish line, which he reached in a mere 9.83 seconds, breaking the world record by a full tenth of a second. In less than ten seconds Ben Johnson had become an international celebrity. He would soon sign commercial endorsement contracts worth millions of dollars.

Meanwhile, Carl Lewis, who had equaled the world record of 9.93 only to finish second, was livid. Although he refused to name names, he made it clear that he thought Johnson was taking illegal, performance-enhancing drugs. Although many dismissed Lewis’ charges as sour grapes, he was not alone in his suspicions.

On the track circuit, Johnson’s highly sculptured muscles and yellow-tinged eyes, two indications of steroid use, had earned Johnson the nickname “Benoid.” However, as his coach, Charlie Francis, was quick to point out, Johnson had passed innumerable drug tests.

In 1985 Johnson himself told Canada’s Athletics magazine, “Drugs are both demeaning and despicable and when people are caught they should be thrown out of the sport for good. . . . I want to be the best on my own natural ability and no drugs will pass into my body.”

As 1988 began, Johnson seemed to have a lock on the Olympic gold medal. But then disaster struck. In February, he pulled a hamstring muscle. In May, he reinjured his leg. In June, he broke away from Charlie Francis for the first time. However, a few weeks later they reconciled and Johnson returned to competition in time to win the Canadian Olympic trials.

On August 17 in Zurich, the site of Johnson’s first victory over Lewis three years earlier, the two met again for the first time since the Rome world championships. As usual, Johnson broke in front, but this time Lewis mowed him down to win with a time of 9.93 seconds. Calvin Smith was second at 9.97 and Johnson third at 10.00. Five days later in Cologne, Johnson was again beaten into third place, this time by Smith and Dennis Mitchell.

While Johnson retreated to Canada for a final month of training, Lewis was installed as the overwhelming favorite to become the first male sprinter to retain his Olympic title. Johnson dismissed this growing consensus. “When the gun go off,” he said, “the race be over.”

In Seoul, Lewis appeared to be in perfect form. He registered the fastest time in each of the first two rounds: 10.14 and 9.99. Johnson, meanwhile, caused a minor sensation in the second round. The rules stated that the top two finishers in each of the six heats would advance to the semifinals, as would the four fastest of the remaining runners. Johnson, misjudging the size of his lead, eased up long before the end, and dropped to third behind Linford Christie and Dennis Mitchell. Fortunately, Johnson’s 10.17 allowed him to advance anyway.

F. Carlton Lewis (USA) 9.92 OR

The semifinals were held the following day, Saturday, at noon. Lewis won the first heat in 9.97. In the second, Johnson was called for a false start, a ruling that infuriated him. Still, he managed to control his anger and win the race in 10.03 despite running into a 1.2-meters-per-second head wind.

Less than an hour and a half later, the eight finalists met at the starting line. Carl Lewis was in lane 3, Ben Johnson in lane 6. They were separated by Linford Christie and Calvin Smith. By now Johnson’s muscles were so highly developed that, as he waited for the sound of the starter’s pistol, they seemed to be separate beings on the verge of exploding out of his skin. As expected, Johnson charged into the lead immediately.

On May 5, 1987, Carl Lewis’ father had died of cancer. At the funeral, Carl had reached into his pocket and pulled out the gold medal he had earned for winning the 100 meters in 1984. He placed the medal in his father’s hands and said, “I want you to have this because it was your favorite event.” Noting his mother’s surprise, he added, “Don’t worry, I’ll get another one.”

Now, halfway through the 1988 final, he glanced to his right, saw Ben Johnson five feet ahead of him, and was convinced that he could catch him. At the 80-meter mark Lewis looked over again and discovered that he was still five feet behind. This time he knew the race was lost. “Damn,” he thought. “Ben did it again. The bastard got away with it again. It’s over, Dad.”

Just before the finish line, Johnson stared back at Lewis and thrust his right arm into the air, his index finger pointed to the sky.

His time was an amazing 9.79.

Lewis, convinced that Johnson was on steroids, wanted to protest, but held his tongue. As he later wrote in his autobiography, Inside Track, “I didn’t have the medal to replace the one I had given [my father], and that hurt. But I could still give something to my father by acting the way he had always wanted me to act, with class and dignity.”

He shook Johnson’s hand and walked away, ignoring the taunts of a group of Canadian fans who chanted, “When the gun go off, the race be over.”

Johnson accepted the accolades of the crowd, appeared live on Canadian television, and then went off to doping control where he required one and a half hours and several beers to produce a urine sample. Afterward he spent over an hour in a sauna, then celebrated by eating half of a cream cake given to him by his mother, dining with friends at an Italian restaurant, and visiting a disco.

Back in Canada, the population was in ecstasy. In the 12 Olympics prior to the boycotted Games of 1980 and 1984, Canada had averaged one gold medal per Olympics. Its last track-and-field gold had come in 1932. The headline in the Toronto Star summed up the mood of the nation: “Ben Johnson-a national treasure.”

Meanwhile, Johnson’s urine sample was delivered to the Olympic Doping Control Center, numbered, and divided into two parts labeled “A” and “B.” On Sunday, the testing center, not knowing whose urine they were examining, discovered that the “A” sample contained steroids. This information was passed on to Prince Alexandre de Merode of Belgium, the chairman of the I.O.C.’s medical commission. He matched the sample to a list of athletes’ numbers and became the first per- son to learn that the guilty party was Ben Johnson.

De Merode wrote a letter to the Canadian team, which was delivered at 1:45 a.m., Monday. At 7:00 a.m., Carol Anne Letheren, the Canadian chef de mission, informed Johnson of the positive test. Three hours later, with Canadian representatives in attendance, the “B” sample was tested and it too registered positive.

At 3:30 Tuesday morning, Letheren revisited Johnson to collect his gold medal. “We love you,” she told him, “but you’re guilty.”

At 10:00 a.m., the I.O.C. called a press conference and issued the following statement: “The urine sample of Ben Johnson (Canada-Athletics-100 meters) collected on Saturday, 24th September 1988 was found to contain the metabolites of a banned substance namely stanozolol (anabolic steroid)

The I.O.C. Medical Commission recommends the following sanction: disqualification of this competitor from the Games of the XXIV Olympiad in Seoul. Of course, the gold medal has been withdrawn by the I.O.C.”

Although Johnson was the 43rd Olympic athlete to be dis- qualified because of drugs since testing began in 1968, he was the first “big fish” to be caught. His disgrace was front-page news all over the world. Initially, Johnson denied having taken steroids. Charlie Francis claimed that Johnson was a victim of sabotage, that he had been given a spiked drink. Francis even hinted that agents of Carl Lewis had been responsible.

The Canadian government, to its great credit, wasted no time in ordering an investigation into the use of banned substances by Canadian athletes, including several of John- son’s sprinting teammates and a number of weightlifters who tested positive before the Games and were not allowed to travel to Seoul.

The investigation, much of which was televised live, became known as the Dubin Inquiry in honor of the man in charge of the hearings, Charles Dubin, an associate chief justice of the Ontario Supreme Court.

Testifying before the Dubin Commission, Charlie Francis and Johnson’s doctor, George (Jamie) Astaphan, revealed that the sprinter began taking steroids in November 1981 because Francis convinced him that everyone else was taking them and that if he didn’t, he would be left behind.

Over the next seven years, Johnson took the anabolic steroids Dianabol, stanozolol, and furazabol, as well as testosterone, diuretics, which he used as masking agents, and human growth hormone, which was made from human cadavers. Although Astaphan had once labeled a bottle of steroids “Do Not Take Within 28 Days of Competition,” he apparently gave Johnson an injection only 26 days before the Olympic final.

The Dubin Commission concluded that this injection contained Winstrol-V, a stanozolol compound used to fatten cattle before they are sent to market.

On June 12, 1989, Johnson himself appeared before the Dubin Commission. He admitted taking steroids and lying to the public when he said he hadn’t. The following day, he was asked if he had any message for young athletes who had considered him their idol. With tears in his eyes, he replied, “I want to tell them to be honest and don’t take drugs. It happened to me. I’ve been there. I know what it’s like to cheat.”

Three months later, the I.A.A.F., in a controversial decision, retroactively rescinded Johnson’s 1987 world record even though he had passed the drug test in Rome. Johnson served out his standard two-year suspension and returned to competition in 1991.

However, his times were not what they had been in his drug-augmented heyday. Johnson qualified for the 1992 Canadian Olympic team but was eliminated in the semifinals at the Olympics.

Following a meet in Montreal on January 17, 1993, Johnson again tested positive for drugs-this time excessive levels of the male hormone Testosterone-and he was banned for life. Although he had passed similar tests two days before and four days after the Montreal meet, Johnson chose not to appeal the ban.

The 1988 gold medal, which Johnson lost, did go to Carl Lewis after all, raising Lewis’ career total to six golds and one silver.

if he had any message for young athletes who had con- sidered him their idol. With tears in his eyes, he replied, “I want to tell them to be honest and don’t take drugs. It hap- pened to me. I’ve been there. I know what it’s like to cheat.”

Three months later, the I.A.A.F., in a controversial deci- sion, retroactively rescinded Johnson’s 1987 world record even though he had passed the drug test in Rome. Johnson served out his standard two-year suspension and returned to competition in 1991. However, his times were not what they had been in his drug-augmented heyday. Johnson qualified for the 1992 Canadian Olympic team but was eliminated in the semifinals at the Olympics.

Following a meet in Montreal on January 17, 1993, Johnson again tested positive for drugs-this time excessive levels of the male hormone Testosterone-and he was banned for life. Although he had passed similar tests two days before and four days after the Montreal meet, Johnson chose not to appeal the ban.

The 1988 gold medal, which Johnson lost, did go to Carl Lewis after all, raising Lewis’ career total to six golds and one silver.

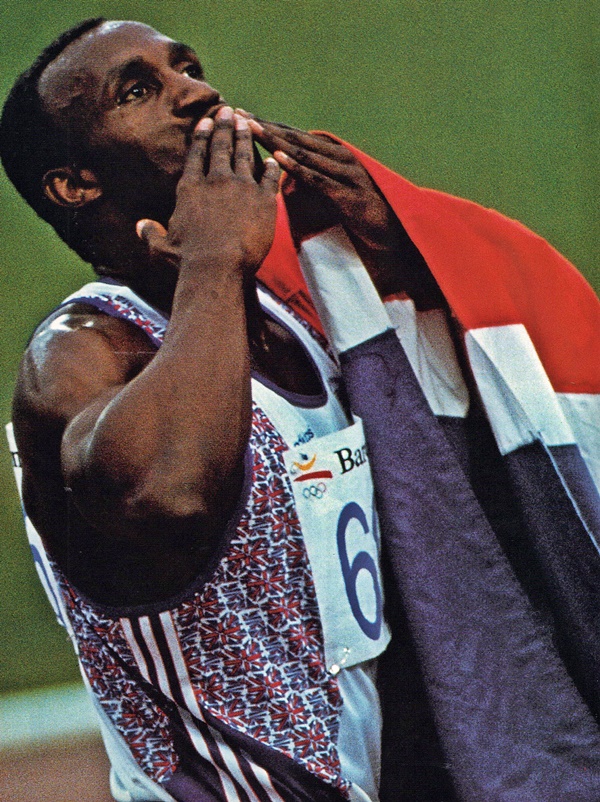

1992 Barcelona

Linford Christie (GBR) 9.96

Ben Johnson was not the only Jamaican-born sprinter who tested positive for prohibited drugs at the 1988 Olympics. Linford Christie’s doping test revealed traces of the banned stimulant pseudoephedrine. But because the amount was so small, Christie was not disqualified or otherwise punished. The vote of the I.O.C. medical commission was 11-10.

Linford Christie (GBR) 9.96

On August 25, 1991, Christie was one of the entrants in one of the greatest 100-meter races of all time the world championship final in Tokyo. Carl Lewis won that race, setting a world record of 9.86. He was followed by Leroy Burrell at 9.88, Dennis Mitchell at 9.91, Christie at 9.92, Frank Fredericks at 9.95, and Raymond Stewart at 9.96-the first and only time that six runners have beaten ten seconds in one race. Christie was so discouraged by the result that he considered retiring.

Christie had a mixed reputation. On the one hand, he was reasonably popular with the public and was voted Britain’s sexiest athlete in 1991. On the other hand, his defensive and hypersensitive demeanor earned him less respect with the press and with fellow athletes. As quarter miler Derek Redmond put it, Christie was “Britain’s best-balanced athlete, because he has a chip on both shoulders.”

Christie’s Barcelona chances were improved when Lewis, winner of every major championship race since 1983, was weakened by a virus and placed only sixth at the US Olympic trials, qualifying only for the 4 x 100-meter lay and the long jump.

Meanwhile, Christie, at age 32, was having his best sea- son ever. His only loss was by 1/100 of a second to Olapade Adeniken. However, Christie still had to overcome former world record holder Leroy Burrell, who had beaten him ten straight times over the past three years. In the Olympic quarterfinals, Christie finally broke that streak, edging Burrell 10.07 to 10.08 in the last heat. The following day, running into a 1.2-meters-per-second head- wind, Burrell beat Christie 9.97 to 10.00 in the first semifinal.

The second semi was won by Fredericks in 10.17.

In the final, Burrell was charged with a false start even though he never left his blocks. Distressed, he was never a factor in the race. After a second delay, when Mitchell signaled that he was not ready, the runners finally took off.

Haitian-born Bruny Surin grabbed the early lead and held it for 40 meters. Over the next 20 meters Christie caught first Fredericks and then Surin. By the 60-meter mark he was in first place and pulling away.

Linford Christie is, by four years, the oldest man to win the Olympic 100 meters. Fredericks became the first black African to medal in the event, and, far from the hoopla and medal attention, Ray Stewart became the first man to run in three 100-meters finals.

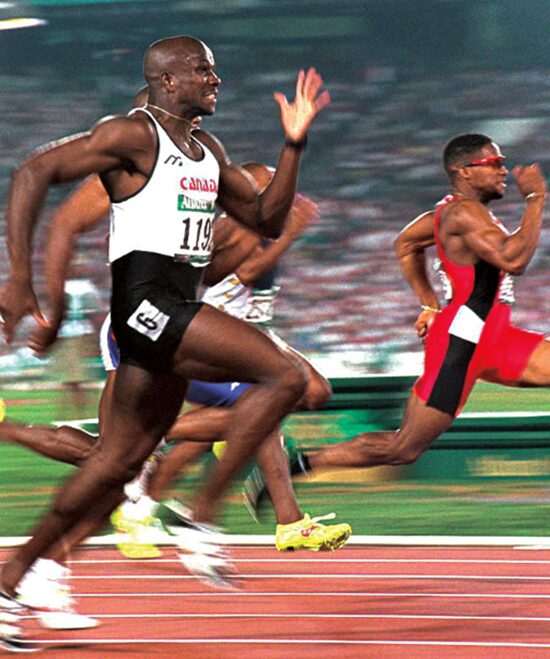

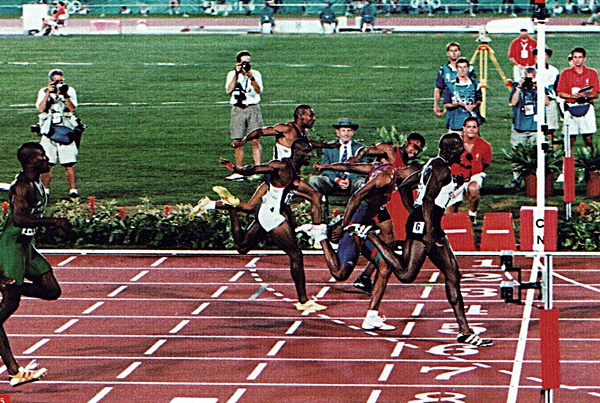

1996 Atlanta

Donovan Bailey (CAN) 9.84 WR

Donovan Bailey was born in Manchester, Jamaica, December 16, 1967, and moved to Canada when he was thirteen years old. In high school and college his favorite sport was basketball, but he ran track as well because it was a good way to meet girls. He graduated from Sheridan College in Toronto with a degree in economics and went to work as a marketing consultant for a brokerage firm. Later he created a successful business importing and exporting clothes.

Donovan Bailey (CAN) 9.84 WR

He did no competitive running for six years, but returned to the sport in 1991 because he knew he was naturally gifted. Still, prior to 1994, his best time was 10.36.

Under the direction of coach Dan Pfaff, Bailey progressed quickly and in 1995 he won the world championship with a time of 9.97. However the 1996 season saw others capturing the headlines.

On June 1, Ato Boldon ran a 9.92; two weeks later, Dennis Mitchell matched that time. Both of them beat Bailey in Stockholm on July 8. On July 3, Frank Fredericks clocked a 9.86 into the wind for the fastest wind-adjusted time in history. Fredricks completed the pre-Olympic season undefeated.

In Atlanta, Boldon won his quarterfinal heat in 9.95. Two heats later, Fredericks ran a 9.93: the fastest non-find time ever recorded. The following evening, Fredericks won the first semifinal in 9.94, with Bailey, after a false start, placing second in 10.00. The second semifinal was won by Boldon in 9.93. Mitchell was second at 10.00 and third place was taken by defending champion Linford Christie who, at age 36, was already a grandfather.

The final was scheduled to start at 9 p.m., but it would be several minutes before the 10-second race was finally concluded. First Christie false started. Then Boldon false started. Then Linford Christie was charged with a second false start and was disqualified.

It was the first time in his long career that he had suffered such a fate. Christie did not go quietly, arguing with the officials and, while the seven remaining finalists waited, refusing to leave the track.

Finally, the track referee, John Chaplin, showed him the red marker indicating disqualification and Christie retreated into the tunnel, throwing his shoes into a trashcan. On the fourth try, the runners broke cleanly. Bailey, as usual, was the slowest out of the blocks. Mitchell showed in front first, then Boldon.

At 60 meters, Frank Fredericks took over the lead, but by this time Bailey, who had been fifth at 40 meters, was running an incredible 27 miles per hour (12.1 meters per second). He shot past the others and crossed the finish line in world record time. The race was so fast that Dennis Mitchell had the unfortunate and unprecedented experience of breaking ten seconds and not winning a medal. While Donovan Bailey set off on a victory lap, Linford Christie rather crudely ran past the stands himself, waving to the spectators who were giving Bailey a standing ovation. Even then, Christie’s career of controversy was not over. In July 1998 he won a libel suit against a journalist who accused him of taking steroids.

After the judgment, Christie told the press, “I am living proof that success achieved after hard, natural, drug-free work lasts so much longer and is so much sweeter.” Seven months later, at a meet in Germany, he tested positive for the steroid nandrolone.

This was the story of the fastest athletes of the past 100 years to which I referred in the book of the great historian David Wallechinsky, “The Complete Book of the Summer Olympic Games” / 2000 edition / The Overlook Press Woodstock & New York / Pages: 2-16

The evolution of the most spectacular race in all sports, perhaps in terms of duration within the limit of no more than 9-10 seconds, the emotions, the speed of the competitors in front of the testimony of thousands of witnesses in the stands of the stadium and millions of others from TV screens.

Of course, the new century will witness even faster athletes under 10 seconds like in 2000 (Sydney) by Maurice Greene (USA) – 9.87, in 2004 (Athens) by Justin Gatlin (USA) – 9.85, in 2020 (in Tokyo) by Marcell Jacobs (Italy) – 9.80 , and above all the world will witness the fastest man on the planet of all time, Usain Bolt, the three-time Olympic champion winner, with science-fiction times: in 2008 (Beijing): 9.69; in 2012 (London) 9.63; in 2016 (in Rio de Janeiro) 9.81! proving to the whole world so far that he, the Jamaican is the King of the 100 m sprint!

BELOW IS THE LINK FOR THE FIRST PART OF THE ARTICLE:

By: Pjerin Bj

New York: January 3, 2025

_____________________

Sports Vision +Plus / Champions Hour in activity since 2013

Discover more from Sports Vision +

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.