The Fastest Men of the Century in the 100 meters of the Olympic Games! | Part One (1896-1936)!

Intro

In the realm of human physicality, there exists a rare breed of athletes who defy the boundaries of mortal speed. The 100m sprint, the quintessential test of velocity, has crowned its share of champions who have tapped into the very essence of speed, transporting us to a future where human potential knows no limits.

Imagine witnessing a spectacle that warps the fabric of time and space – athletes exploding off the starting line, their movements a blur as they devour the distance, approaching the speed of light. This is the realm of the 100m sprint, where the world’s fastest humans converge to push the boundaries of physical possibility.

In the fleeting instant it takes for a 100m sprinter to cross the finish line, we glimpse the awe-inspiring potential of human physiology. Like shooting stars, these athletes blaze across our collective consciousness, their achievements etched into the annals of Olympic history. As we marvel at their cosmic speed, we are reminded that, even if only for a moment, they have transcended the limitations of mortal men and women, entering a realm where time and space are but distant memories.

In the realm of human physicality, where athletes defy the boundaries of mortal speed, the 100m sprint is the quintessential test of velocity. Like cosmic bolts of lightning, they streak across the track, leaving all else in their shadow. Imagine witnessing a spectacle that warps the fabric of time and space – sprinters exploding off the starting line, their movements a blur as they devour the distance, approaching the speed of light. For a fleeting instant, they transcend the limitations of mortal men and women, entering a realm where time and space are but distant memories.

From Jesse Owens to Usain Bolt, this is the domain of Olympic track and field legends, who have continually redefined the frontiers of speed, inspiring generations to chase the impossible.

1. Part One (1896 – 1936)

From Thomas Burke to Jesse Owens

1896 Athens

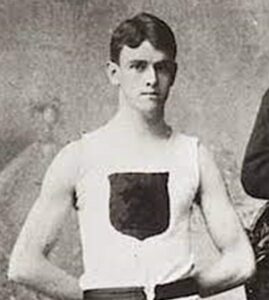

Thomas Burke (USA) 12.00

The very first race of the modern Olympics was the open- heat of the 100-meter dash. It was won by Frank Lane Princeton in the time of 12.00 seconds. The European crowd was fascinated by the “crouch” start of the Americans, as Thomas Curtis and quarter-mile specialist Thomas Burke, both of Boston, won the other two qualify heats.

1896 – Thomas Burke / USA 12.00

Their teammates celebrated by chanting, “B.A.! Rah! Rah! Rah!”

The Greek spectators had never heard organized cheering before. They liked it so much that the Boston men were called on to repeat it frequently through the remainder of their stay in Athens.

The first two finishers in each of the heats qualified for the final four days later, but Curtis chose not to start, preferring to save himself for the 110-meter hurdles, which was the next race.

Burke, who had registered the fastest time (12.0) in the heats, equaled his time in the final and defeated Hofmann by two meters. The other runners were bunched four meters further back.

Although Hofmann was a champion sprinter, his athletic specialty was actually rope climbing.

Th. Burke is the first Olympic champion in 1896

Thomas Burke also won the Olympic 400 meters final. The following year he served as the official starter for the inaugural Boston Marathon. He later became a lawyer and also wrote part-time for the Boston Journal and the Boston Post. Burke died on Valentine’s Day, 1929, at the

age of 53.

1900 Paris

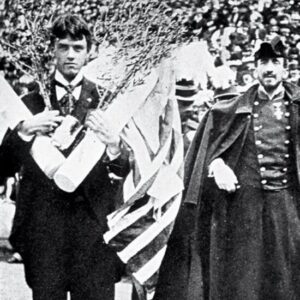

Frank Jarvis (USA) 11.0

The American runners had never competed before on a grass track, but this didn’t prevent Jarvis of Princeton and Tewksbury of Pennsylvania from equaling the world record of 10.8 in the heats and semifinals, respectively.

American athlete Frank Jarvis

Despite these performances, the clear favorite was 5-foot 7-inch Arthur Duffey of Georgetown University, who had defeated both Jarvis and Tewksbury in London the previous week. As expected, Duffey burst into the lead and seemed well on his way to victory, when he suddenly began to wobble and fell to the ground at the 50-meter mark, the victim of a strained tendon in his left leg.

Jarvis went on to win by about two feet.

Duffey later told the press, “I do not know why my leg gave way. I felt a peculiar twitching after going twenty yards. I then seemed to lose control of it, and suddenly it gave out, throwing me on my face. But that is one of the fortunes of sport, and I cannot complain.”

In 1902 Duffey ran 100 yards in 9.6 seconds, setting a world record that stayed in the books for 24 years. Later he became a columnist for the Boston Post.

1904 St. Louis

Charles “Archie” Hahn (USA) 11.0

Archie Hahn, “The Milwaukee Meteor,” had already won the 60-meter and 200-meter dashes when he settled down for the final of the 100. Running into a heavy wind, he shot out to a fast start, had a one yard lead by the 20-meter mark, and held off the fast-finishing Louisville sprinter Nate Cartmell to win by almost two yards.

Charles “Archie” Hahn (USA) 11.0

Hahn was only 5 feet 5 inches tall and weighed about 130 pounds. He did not take up track until he was 19 years old. The following year, 1900, he was recruited by representatives of the University of Michigan, who saw him win a race at a county fair.

1906 Athens

Charles “Archie” Hahn (USA) 11.2

William Eaton of Boston recorded the fastest time in the semifinals (11.2), but in the final Hahn, with a quick start, led the whole way and won by a yard. Back in the United States, Hahn studied law at Michigan, but never practiced his profession. Instead he devoted his life to coaching younger runners. His book How to Sprint is still considered a classic text.

1908 London

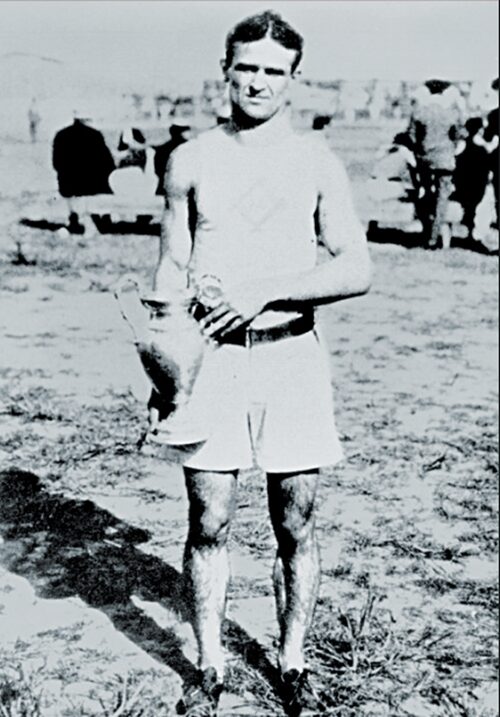

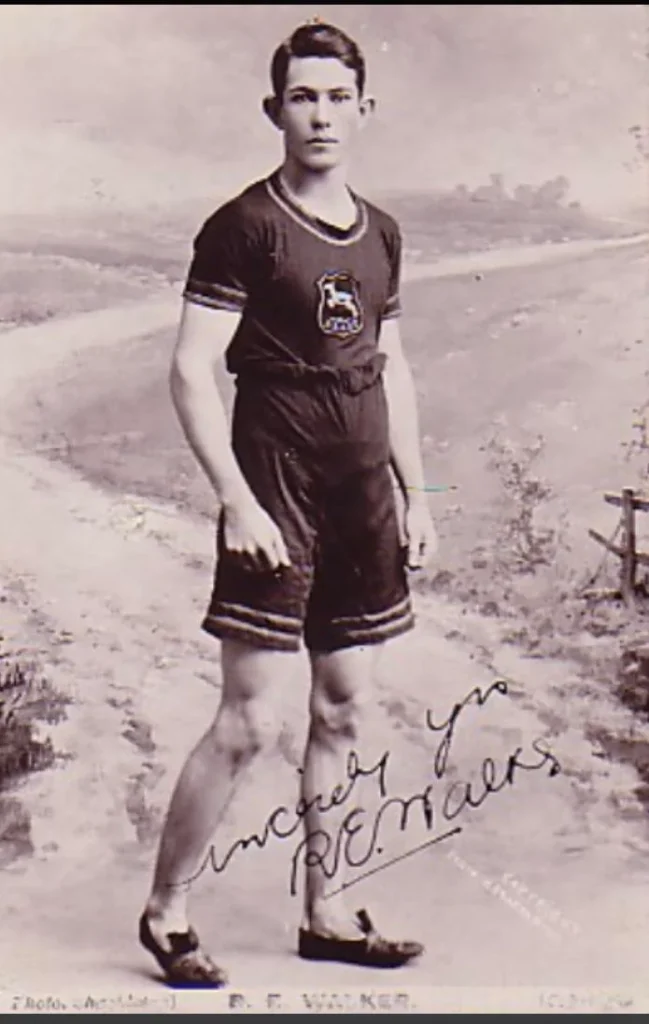

Reginald Walker SAF 10.8 EOR

In 1908 the excitement surrounding the 100-meter race rivaled that of the marathon. The tension was heightened by the fact that only the winner of each heat advanced to the next round. The favorites, James Rector, a University of Virginia student from Hot Springs, Arkansas, and Bobby Kerr, the Irish-born Canadian champion, did not disappoint their supporters in the opening heats.

Reginald Walker SAF 10.8 EOR

Rector was particularly impressive, tying the Olympic record of 10.8 seconds. He equaled this time in the semifinals, but so did Reggie Walker, a 19-year-old clerk from Durban. Arriving three weeks before the Olympics, Walker lost to Kerr in the final of the British A.A.A. championship.

Nevertheless he caught the eye of the famous coach Sam Mussabini, who took the young man under his wing and spent the next couple of weeks working with him on his start. Indeed, according to Rector, Mussabini asked Rector himself to help Walker, which he did.

This last-minute training worked wonders. Running on the inside lane, Walker stormed into an early lead, gave way to Rector at the halfway point, and then was able to pull ahead once again to win by a “long yard,” with Rector holding on to second by mere inches.

The 5-foot 7-inch, 130-pound Walker, who had been previously unknown to the general public, became an instant hero, as the crowd of 49,000 cheered wildly and threw their hats and programs into the air, while friends and officials competed for the right to carry the embarrassed South African on their shoulders.

James Rector later described the scene: “The bands were furiously playing national airs, while the bookmakers were calling their bets and the whole stadium seemed to be disordered.” In the words of one U.S. newspaper, “The Englishmen were gratified to see the monotonous succession of American victories broken by a British, even if he was a colonist.”

1912 Stockholm

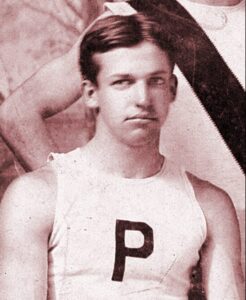

1. Ralph Craig (USA) 10.8

Ralph Craig of the University of Michigan was considered the pre-Olympic favorite until he was beaten in the U.S trials by Howard Drew, a strong black student from Springfield, Massachusetts.

Ralph Craig (USA) 10.8

In the first round in Stockholm, Donald Lippincott, the star of the University of Pennsylvania track team, set an Olympic record by winning his heat in 10.6 seconds. The semifinals were run with only the winner of each race advancing to the final.

The Americans showed their strength by winning all five of the heats in which they were entered. Unfortunately, Drew strained a tendon just before the finish of his heat and, despite qualifying, was unable to start in the final.

The final was marred by seven false starts, the first three by Craig. After one false start, Craig and Lippincott raced all the way to the finish line.

At the eighth try a clean break was made, with Patching taking the early lead. Craig caught him at the 60-meter mark and went on to win by two feet. Thirty-six years later, Craig, by then a wealthy 59-year-old industrial engineer, reappeared at the London Olympics as an alternate on the U.S. yachting team and was chosen to carry the United States’ flag at the Opening Ceremony.

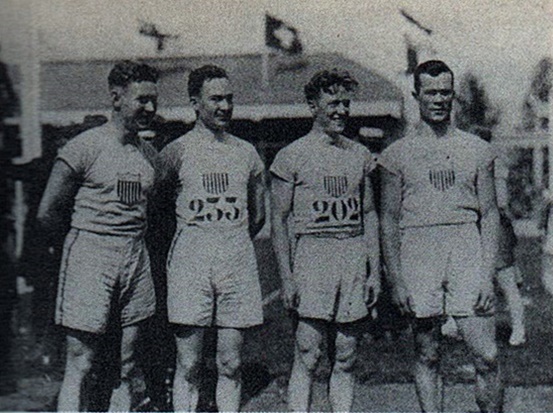

1920 Antwerp

Charles Paddock (USA) 10.8

Charley Paddock was born in Gainesville, Texas, on August 11, 1900.

A sickly child, he weighed only 71⁄21⁄2 pounds at the age of 7 months.

His parents moved to Southern California for his health, eventually settling in Pasadena. The change of climate must have done the trick, because by age 15, Charley was a barrel-chested 170-pounder with big strong legs and a sprinter’s body.

Charles Paddock (USA) 10.8

He loved to run long distances, but his father convinced him to concentrate on the 100 yards and the 220 yards Paddock came to international attention in 1919 when he won both metric sprints at the Inter-Allied Games in Paris, with times of 10.8 and 21.6. Charley was a great crowd-pleaser, who delighted photographers with a flying finish in which he would leap at the tape from about 12 feet out, with his arms flung wide.

The semifinals of the Olympic championship were held in the early morning on Monday, August 16. The first heat was won by Guyanese-born Harry Edward and the second by Charley Paddock, both in 10.8.

Scholz and Murchison had also run 10.8 in the earlier rounds. All four Americans qualified for the final and spent the next few hours together, waiting anxiously for their late afternoon race.

The blond-haired Murchison kept muttering, half to himself, “I’m going to win. I’ve known it all along….

I can trim any sprinter who ever lived.” The others tried to ignore him. Just before it was time to take the field, the four runners were approached by coach Lawson Robertson, who said, “What you fellows need to warm up is a glass of sherry and a raw egg.”

Murchison, Scholz, and Paddock were horrified by the suggestion, but when Stanford’s Morris Kirksey agreed to try the drink, the others feared it would give him a psychological advantage to be the only one to follow the coach’s advice, so they guzzled down the strange concoction as well.

Like many athletes, Charley Paddock followed a set of good-luck rituals. On the way to the starting line he would knock on “a friendly piece of wood.” When called to his mark, he would put his hands far across the starting line and then draw them slowly back before the second call of “get set.” Paddock was the last to stoop to his mark at the starting line of the 1920 100-meter final.

The assistant starter, unaware of Charley’s ritual, ordered him in French to pull back his hands, which he was actually already in the process of doing. The starter then called out “prêt,” the French equivalent of “get set.”

Murchison misinterpreted the exchange and thought the runners had been ordered to stand up, so he was just beginning to relax and rise when the gun went off. He was left 10 yards behind. Kirksey took the early lead, but at the halfway mark Scholz had a two- foot advantage, with Edward in second. Then Kirksey surged ahead again, with Paddock at his shoulder. In the words of Charley Paddock: “Then I saw the thin white string stretched to the breaking point in front of me.

I drove my spikes into the soft cinders and felt my foot give way as I sprang forward in a final jump for the tape…. There was nothing more I could do. My eyes closed as my chest hit the string and when I opened them, my feet were on the ground again and I was yards ahead of the field.

I did not know if I had been in front when the string was broken.

Charley Paddock; Jackson Scholtz; Loren Murchinson and Morris Kirksay together before the 100m final in 1920. Six days later they teamed up to win 4×100 meter relay for USA

I dared not ask.” In fact, Charley Paddock had won the race by 12 inches. “My dream had come true,” he later wrote, “and I thrilled to the greatest moment I felt that I should ever know…. The real pleasure had been in the anticipation and in that single moment of glorious realization.

1924 Paris

Harold Abrahams (GBR) 10.6 EOR

The story of Harold Abrahams’ victory in Paris in 1924 is well told in the beautiful film Chariots of Fire. Unfortunately, despite its claim of being “a true story,” the film contains several factual distortions.

Harold Abrahams (GBR) 10.6 EOR

Abrahams did not race around the great courtyard of Trinity College at Cambridge. (It was Lord Burghley who did that.) He did not look at the 100-meter contest as a chance to redeem himself after his failure in the 200, since the running of the 100 actually preceded the 200 in real life.

Although Abrahams did feel himself an outsider because he was Jewish, a much more importarit motivating factor in his quest for victory was a desire to do better than his two older brothers, both of whom were well-known athletes and one of whom had represented Great Britain in the long jump at the 1906 and 1912 Olympics.

Abrahams himself had competed in the 100 and 200 meters in Antwerp in 1920, but had been eliminated in the quarter-finals. In the year preceding the Paris Olympics, Abrahams came under the direction of Sam Mussabini, who had successfully coached Reggie Walker to victory in 1908. Among other things, Mussabini stressed to Abrahams the importance of the length and number of his strides. During practice sessions Abrahams would place pieces of paper on the track, to indicate where each stride should end.

Then he would try to pick them up on his spikes as he ran. He always carried with him a piece of string the length of his first stride. Before a race he would pull out the string, measure forward from the starting line, and make a mark on the track where his first step should land.

Abrahams was also a proficient long-jumper. One month before the Olympics he leaped 24 feet 21⁄21⁄2 inches (7.38 meters) to set an English record that lasted until 1956. For this reason he was chosen to represent Great Britain in the long jump as well as the 100, 200, and 4 x 100 relay. When an anonymous letter appeared in the Daily Express, criticizing the decision to enter Abrahams in the long jump, few people knew that the letter had been written by Harold Abrahams himself. He made his point and was excused from that event.

Despite his great feats, the 6-foot 21⁄2-inch, 175-pound Abrahams was considered a long shot in comparison to the U.S. team, which included defending champion Charley Paddock as well as Antwerp finalists Jackson Scholz and Loren Murchison. On June 18, 1921, Paddock had stunned the track world by running 110 yards (which is actually longer than 100 meters) in the unheard-of time of 10.2 seconds, a record that remained unbeaten for 29 years.

Although the Americans were the favorites, it was Harold Abrahams, running faster than he had ever run before, who registered the fastest times in the early heats, tying the Olympic record (10.6) twice, in the quarterfinals and the semifinals, where he overcame an awful start. For the first time Abrahams realized that he had a chance to win the Olympic gold, and for the first time he began to feel the pressure.

For the next 33⁄44 hours, as he waited for the final, he “felt like a condemned man feels just before going to the scaffold.” As he went to his mark at 7:05 p.m. on July 7, Abrahams recalled Sam Mussabini’s final words of advice:

“Only think of two things-the report of the pistol and the tape. When you hear the one, just run like hell till you break the other.”

After a perfect start, the runners ran almost even for the first 40 or 50 meters, but then Abrahams began to move ahead, gaining with each stride until he crossed the tape with a two-foot victory.

Harold Abrahams is a perfect example of an athlete who peaks at exactly the right moment. After that day at the Stade Colombes in Paris, he never raced well again. The following year he injured his thigh while long-jumping and retired from competition forever.

He once wrote, “I wonder if, in a sense, that was not another piece of good bad-luck. How many peo- ple find it almost impossible to retire at the right time. Would I have gone downhill and tried to go on?

That was the deci- sion I never had to make; it was made for me. Rather painfully, but it was made.” Abrahams went on to great success as a radio commentator, lawyer, writer, statistician, and president of the British Amateur Athletic Association.

Arthur Porritt, who took the bronze medal even though he failed to win a single heat, had an even more distinguished career, culminat- ing in a two-year term as Governor-General of New Zealand and more than 30 years as Surgeon to the British royal family. Among his many legacies, Porritt was a vigorous proponent of the doctor’s role as a personal friend to each of his patients.

Until Abrahams’ death in 1978, he and Porritt and their wives had dinner every year at 7:00 p.m. on July 7-the day and the hour of the 1924 100-meter final.

As for Charley Paddock, he acted in a couple of Hollywood films, went into the news- paper business, and became active in local politics in Pasadena.

During World War II he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps and died in a plane crash in Alaska on July 21, 1943. Harold Abrahams mounted his gold medal on a plinth with a plaque engraved with the signatures of the other five finalists of the 1924 100 meters. The gold medal was stolen before Abrahams’ death and never recovered.

In 1989 the rest of his major medals and awards were auc- tioned at Christie’s and purchased by Mohamed al Fayed, who put them on display at his London department store, Harrod’s. Al Fayed’s son, Dodi, who later died in a car crash with Diana, Princess of Wales, had served as execu- tive producer for the film Chariots of Fire.

1928 Amsterdam

Percy Williams (CAN) 10.8

Percy Williams was one of the most popular winners of the Amsterdam Games. Not considered a serious threat by the experts, the slim, almost frail-looking 20-year-old from Vancouver, British Columbia, caught the fancy of the crowd in the second round, when he tied the Olympic record of 10.6.

Percy Williams (CAN) 10.8

This time was matched in both semifinals, first by Bob McAllister, “The Flying Cop” of New York City, who bare by held off a slow-starting Williams, and then by Jack London, a Guyanese-born university student who was the first Briton to use starting blocks.

In Amsterdam, Williams was joined by his coach, Bob Granger, a janitor who man- aged the trip by washing dishes on the train to Toronto and working on a freighter to Europe.

He helped Williams practice his starts in his hotel room by racing into a mattress set against the wall. As the six finalists lined up for the deciding race, the 5-foot 6-inch, 126-pound Williams seemed an unifikely bet to become Olympic champion, particularly as he was standing beside the muscular, 6-foot 2-inch, 200- pound London. After two false starts, by Legg and Wykoff (who had gained ten pounds on the boat ride from the United States), the runners were off.

Williams took the lead immediately and kept it the entire way, holding off late rushes by London and Lammers to win by two feet. McAllister pulled a tendon 20 meters from the tape and finished last.

In the days before television, an unexpected winner like Williams could be famous and unrecognized at the same time.

Only a few hours after his Olympic victory, Williams and a friend noticed a large crowd gathered in front of his hotel.

“We joined the mob,” Williams later recalled, “looking over their shoulders. I asked a person in front of me why they were there and he said, ‘We’re waiting for the Canadian runner Williams to come out of the hotel.’

I didn’t tell him who I was. I stood around waiting for him, too, and talking to some of the people-it was much more fun.”

Upon his return to Canada, Williams, who also won the 200 meters, was greeted with an enthusiasm reminiscent of the ancient Greek Olympics. Crossing the continent by train with his mother, he stopped in Montreal, where he was presented with a gold watch. In Hamilton he received a silver tea service and in Winnipeg a bronze statue, a silver cup, and a golden retriever.

When he finally reached Vancouver, a school holiday was declared, and he was met by tens of thousands of cheering fans. He was given a blue Graham- Paige sports car as well as $14,500 for his education.

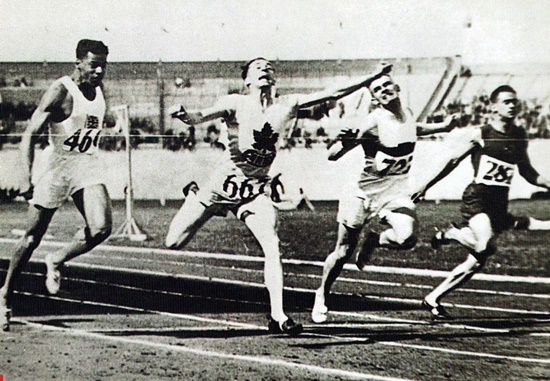

1932 Los Angeles

Thomas “Eddie” Tolan (USA) 10.3 OR

Eddie Tolan was the third University of Michigan athlete to win the Olympic 100 meters gold medal, following in the tradition of Archie Hahn and Ralph Craig. The 5-foot 7-inch Tolan dominated U.S. sprinting from 1929 to 1931, but he was dethroned by Ralph Metcalfe of Marquette University in Milwaukee, who breezed undefeated through the 1932 season.

Thomas “Eddie” Tolan (USA) 10.3 OR

At the U.S. Olympic trials Metcalfe beat Tolan in both sprints and went to Los Angeles as the favorite. But in the second round it was Tolan who set an Olympic record of 10.4. In the final Yoshioka, an excellent starter, took the lead from the first step and held it for 40 meters, when he was caught by Tolan.

Yoshioka faded at 60 meters, while Metcalfe began his famous finishing spurt. He pulled even with Tolan at 80 meters and the two ran neck and neck for the rest of the race, crossing the finish line in a near dead heat.

The favorite Ralph Metcalfe and the winner Thomas “Eddie” Tolan!

Most of the spectators felt that there had been a tie or that Metcalfe had won. Several hours later, seven judges viewed a film of the race and determined that Tolan had crossed the line two inches ahead of Metcalfe.

Current rules state that the first runner to reach the finish line is the winner. So close was the race that if the current rules had been in effect in 1932, Metcalfe would have been the winner.

There were also two also-rans who provoked interest in 1932. The first was Daniel Joubert, a white South African who spoke seven African dialects.

Joubert arrived in Los Angeles in a somewhat weakened condition, having traveled 38 days to get there. Considering his ordeal, it was quite an achievement that he even made the final. The other was Liu Changchun, who marched in the opening day ceremony as the one and only representative of the 400,000,000 people of China.

No Chinese athlete had ever competed at the Olympics. When the Japanese invaded northeastern China and set up the puppet Manchukuo government, they announced that they would send Liu to compete at the 1932 Olympics.

The Foto-finish race of 1932

Liu, a student at Northeastern University, refused. The head of the university, General Zhang Xueliang, then personally financed Liu’s trip to Los Angeles. Liu finished last in his first round heat in both the 100 and 200. He also competed in both events at the Berlin Olympics four years later.

1936 Berlin

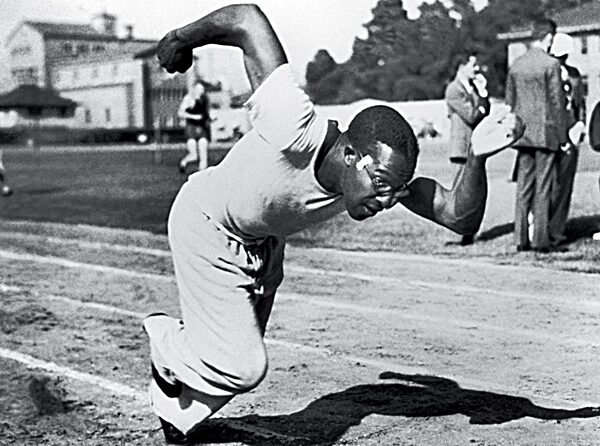

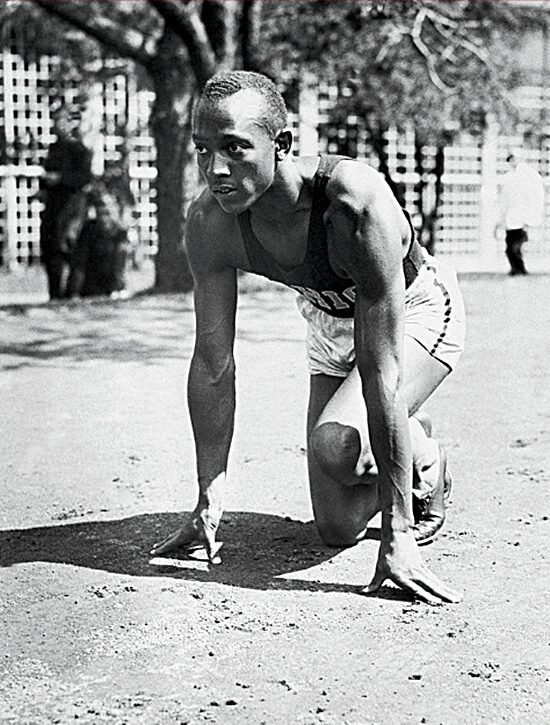

Jesse Owens (USA) 10.3

Jesse Owens assured himself a permanent place in sports history on May 25, 1935, when, while competing at the Big Ten championships at Ann Arbor, Michigan, he broke five world records and equaled a sixth in the space of 45 minutes. At 3:15 p.m. he won the 100-yard dash by five yards in 9.4 seconds to tie the world record. At 3:25 he long-jumped 26 feet 8 inches, breaking the existing world record by six inches.

Jesse Owens, winner of 4 gold medals in the 1936 Olympic

It was his only jump of the day, but it wasn’t beaten for 25 years. At 3:45 he scored a ten- yard victory in the 220-yard dash, clocking 20.3 seconds and bettering the listed record by three-tenths of a second. He was also given credit for lowering the world record in the shorter 200-meter dash. At 4:00 p.m. he flew over the 220-yard low hurdles in 22.6, the first man to beat 23 seconds. En route he also established a record for the 200- meter hurdles. Despite these and other sensational performances, in the following year Owens lost three times to the great Alabama-born sprinter Eulace Peacock.

And it wasn’t until one week before the Olympic trials that Jesse was able to defeat Ralph Metcalfe. But he peaked when he needed to, winning the 100, 200, and long jump at the trials, and he went to Berlin as the favorite in all three events.

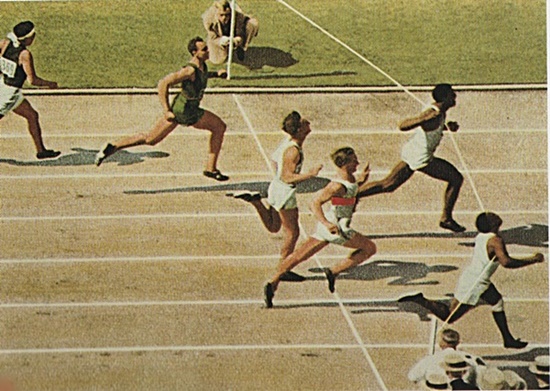

Owens had little trouble living up to expectations. In the first round of the 100 meters he tied the Olympic record of 10.3. In the second round he ran a wind-aided 10.2. Jesse took it easy in the semifinals, winning his heat in 10.4 while Metcalfe won the other in 10.5.

The final saw Owens take the lead from the first stride and pull out to a five-foot lead by the halfway mark. As usual Metcalfe started slow- ly and came on strong in the last 25 meters. He closed the gap, but was still a yard back when Owens broke the tape. Metcalfe, who was elected to the U.S. Congress 34 years later, picked up his second straight 100 meters silver medal, while Osendarp became the first Dutchman to win an individual track and field medal.

Strandberg appeared to be a sure medalist, but he strained a tendon at the 80-meter mark and limped home in last place. Before the week was out, Jesse Owens had earned three more gold medals.

Nazi propaganda had portrayed Negroes as inferior, taunting the United States for relying on “black auxiliaries.” Evidently, though, the message had little effect on the German masses, who considered Owens the hero of Berlin.

Everywhere he went around town he was mobbed by fans seeking his autograph or photograph. They even shoved autograph books through his bedroom window in the Olympic Village while he tried to sleep.

BELOW IS THE LINK FOR THE SECOND PART OF THE ARTICLE

By: Pjerin Bj

New York: January 3, 2025

_____________________

Sports Vision +Plus / Champions Hour in activity since 2013

Discover more from Sports Vision +

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.