Owens’ Olympic Odyssey: Defying Adversity, Inspiring Generations!

Jesse Owens (1913-1980)

US American, track and field athlete!

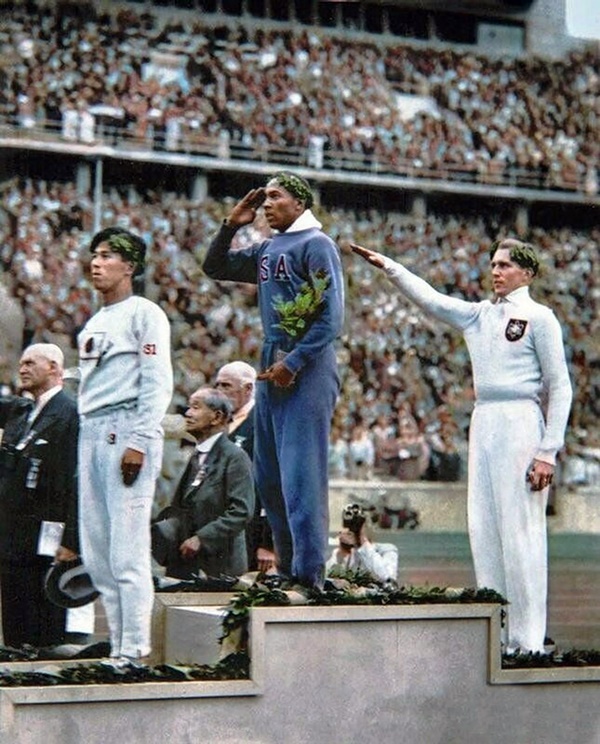

4 gold medals and Olympic Champion in Berlin 1936!

Intro

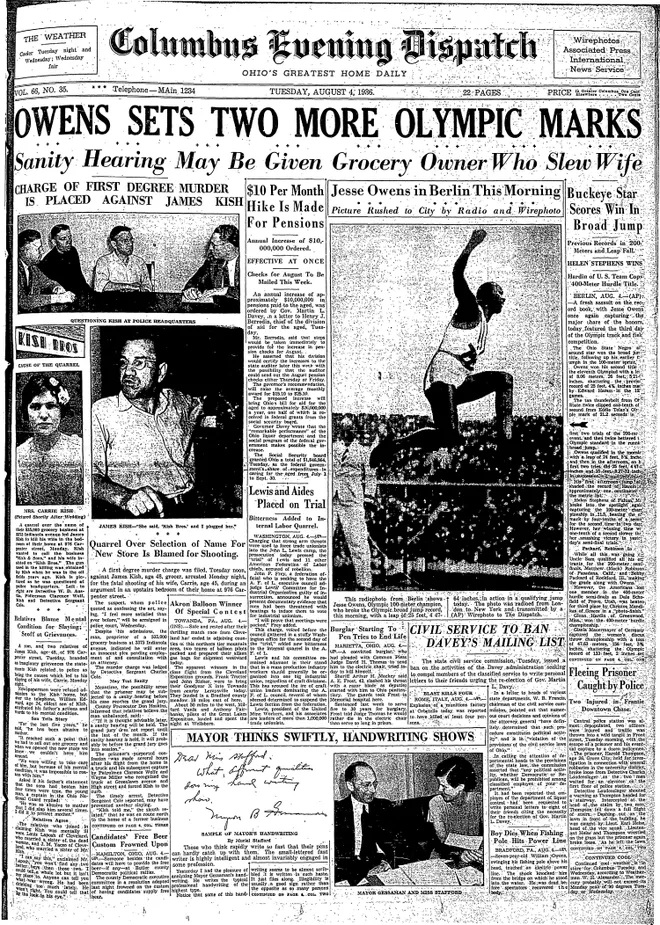

In the sweltering summer of 1936, the world converged on Berlin, Germany, for the Olympic Games. Amidst the Nazi regime’s pomp and propaganda, a young American athlete named Jesse Owens stole the spotlight, shattering records, defying racism, and cementing his legacy as one of the greatest Olympians of all time.

Jesse Owens was more than just an athlete – he was a symbol of hope, a beacon of excellence, and a defiant rebuke to the racist ideologies of his time. Born in the Deep South, raised in the Midwest, and forged in the crucible of competition, Owens’ remarkable life and career continue to inspire generations.

On August 3, 1936, Jesse Owens stepped onto the Olympic Stadium track in Berlin, Germany, and into the annals of history. Over the next 45 minutes, he would rewrite the record books, win four gold medals, and etch his name forever in the hearts of sports fans worldwide. This is the story of Jesse Owens, an American icon and a champion for the ages.

1.

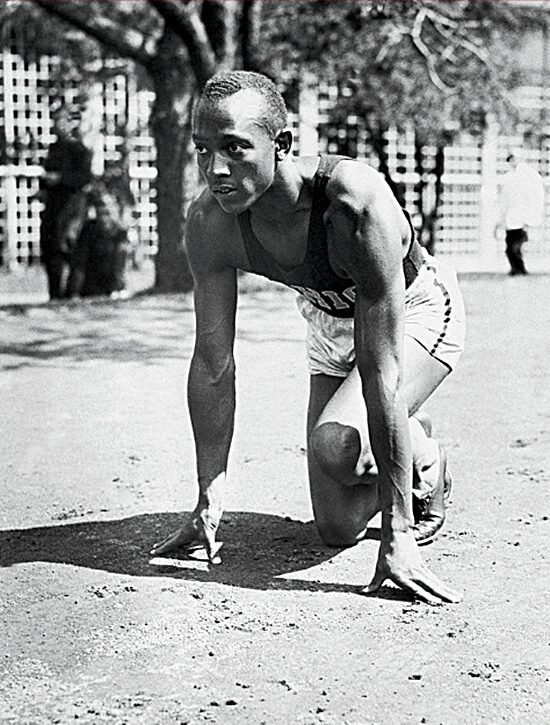

Owens assured himself a permanent place in sports history on May 25, 1935, when, while competing at the Big Ten championships at Ann Arbor, Michigan, he broke five world records and equaled a sixth in the space of 45 minutes.

At 3:15 p.m. he won the 100-yard dash by five yards in 9.4 seconds to tie the world record.

At 3:25 he long-jumped 26 feet 8 inches, breaking the existing world record by six inches. It was his only jump of the day, but it wasn’t beaten for 25 years.

At 3:45 he scored a ten- yard victory in the 220-yard dash, clocking 20.3 seconds and bettering the listed record by three-tenths of a second.

He was also given credit for lowering the world record in the shorter 200-meter dash.

At 4:00 p.m. he flew over the 220-yard low hurdles in 22.6, the first man to beat 23 seconds.

En route he also established a record for the 200- meter hurdles.

Despite these and other sensational performances, in the following year Owens lost three times to the great Alabama-born sprinter Eulace Peacock.

And it wasn’t until one week before the Olympic trials that Jesse was able to defeat Ralph Metcalfe.

But he peaked when he needed to, winning the 100, 200, and long jump at the trials, and he went to Berlin as the favorite in all three events.

2.

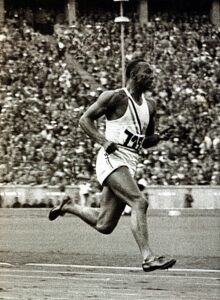

Owens had little trouble living up to expectations. In the first round of the 100 meters, he tied the Olympic record of 10.3. In the second round he ran a wind-aided 10.2. Jesse took it easy in the semifinals, winning his heat in 10.4 while Metcalfe won the other in 10.5.

The final saw Owens take the lead from the first stride and pull out to a five-foot lead by the halfway mark.

As usual Metcalfe started slowly and came on strong in the last 25 meters.

He closed the gap but was still a yard back when Owens broke the tape.

Metcalfe, who was elected to the U.S. Congress 34 years later, picked up his second straight 100 meters silver medal, while Osendarp became the first Dutchman to win an individual track and field medal.

Strandberg appeared to be a sure medalist, but he strained a tendon at the 80-meter mark and limped home in last place. Before the week was out, Jesse Owens had earned three more gold medals.

Nazi propaganda had portrayed Negroes as inferior, taunting the United States for relying on “black auxiliaries.”

Evidently, though, the message had little effect on the German masses, who considered Owens the hero of Berlin. Everywhere he went around town he was mobbed by fans seeking his autograph or photograph.

They even shoved autograph books through his bedroom window in the Olympic Village while he tried to sleep.

3.

Jesse Owens was born September 12, 1913, in Danville, Alabama, the son of sharecroppers and the grandson of slaves.

By the age of 7 he was expected to pick 100 pounds of cotton a day. When he was 9 his family moved north to Cleveland, where Jesse pumped gas and delivered groceries.

After he set national high school records in the long jump, the 100-yard dash, and the 220, he was recruited by 28 colleges.

It was at this point in his life that the 19-year-old Owens first confronted the responsibilities of being a public figure and the need to maintain a positive public image.

Local black newspapers and political leaders took a keen interest in his choice of universities and were critical when he chose Ohio State, a university that had earned a racist reputation.

In 1935, while competing in California, Owens was photographed socializing with a wealthy white woman named Quincella Nickerson.

On July 4, a Cleveland journalist confronted Owens with the fact that he was the father of a 22-year-old daughter and that his newspaper would publish a photograph of the little girl if Jesse did not marry the girl’s mother, Ruth Bolomon. Owens married Ruth the very next day.

The following month, Jesse faced another public relations crisis. While at Ohio State, he had worked as a freight elevator operator and then as a page in the state legislature.

As Owens’ fame grew, it came out that his page “job” had been one at which he had not had to work. Jesse settled the matter by paying back the salary he had received: $159.

4.

There is an enduring myth that after Jesse won the 100 meters in Berlin he was snubbed by Adolf Hitler, who refused to meet Owens after he had personally congratulated three earlier gold medal winners.

Actually, if such a snub did occur, the recipient was not Jesse Owens, but Cornelius Johnson and David Albritton, black Americans who had finished one-two in the high jump the previous day.

Owens was snubbed by a different world leader-Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Although Jesse received tickertape parades in New York City and Cleveland, the President not only failed to invite him to the White House, he never even sent a letter of congratulations.

Owens was also snubbed by the Amateur Athletic Union, which suspended him for refusing to run in a Swedish meet, which he had never agreed to enter.

The A.A.U. also bypassed him for the Sullivan award, which was presented to the best U.S. amateur athlete of the year. In 1935, the year that Jesse Owens set six world records, the award was given to a golfer named Lawson Little. In 1936, the year of Owens’ four gold medals, the award went to Glenn Morris, the Olympic decathlon champion.

After the Olympics Jesse worked as a paid campaigner for presidential candidate Alf Landon. When Landon lost to Roosevelt in a landslide, and after a series of unsuccessful business and work ventures, Owens took a $130-a- month job as a playground instructor in Cleveland.

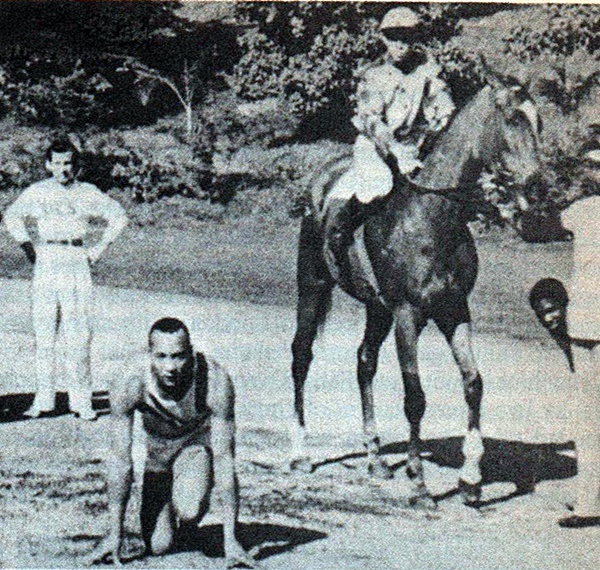

In an attempt to make ends meet, the hero of Berlin, “The Ebony Antelope,” allowed promoters to stage exhibitions in which he raced against horses, dogs, and motorcycles.

Tiring of this, he returned to his job as a playground instructor. Then he lent his name to a chain of cleaning stores which went bankrupt, leaving Owens $114,000 in debt.

In the 1950s he finally achieved financial security when he opened a public relations firm and became a public speaker on behalf of various corporate sponsors.

He developed a repertoire of five basic speeches including ones on religion, patriotism, and marketing for salesmen.

In the words of writer William Oscar Johnson, Jesse Owens had become “a professional good example.”

In 1968 Owens took the side of the U.S. Olympic Committee in its struggle with militant black athletes and two years later he wrote a book called Blackthink, which criticized racial militancy.

However in 1972 he published another book, “I Have Changed”, retracting his earlier criticisms.

After 35 years of pack-a-day cigarette smoking, Jesse Owens died of lung cancer in Tucson, Arizona, on March 31, 1980.

Four years later a street in Berlin was renamed in his honor.

5.

In the end, Jesse Owens filled an important need in American society, first among African-Americans and then among whites: the need for an honest clean-cut hero.

Facts that might have tarnished his image, such as keeping a separate apartment for rendezvous with mistresses, or his 1966 conviction for non-payment of taxes, were ignored.

Jesse eventually gave America what it wanted, inventing the sort of details about his life that the public wanted to hear.

A typical example concerns the apocryphal Hitler snub. At first, Owens denied that it had happened and insisted that he had been treated well by all Germans. But the persistence of the Hitler snub story was so great that Jesse finally stopped denying it and actually incorporated it into his speeches.

Jesse Owens’ celebrity failed to earn him a living, and he was forced to make ends meet by racing against horses, dogs, and motorcycles. He eventually found his place as a “professional good example.”

Would-be Olympic sprint champions might be interested to know the secret of Owens’ success. In 1936 he told one London reporter, “I let my feet spend as little time on the ground as possible. From the air, fast down, and from the ground, fast up. My foot is only a fraction of the time on the track.”.

New York: January 3, 2025

_______________________

Sports Vision Plus+ in activity since 2013

“The Complete Book of The Summer Olympics” (Sydney 2000 Edition) / The Overlook Press Woodstock & New York / David Wallechinsky / Pages: 6-7

Discover more from Sports Vision +

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.