Jurgen Sparwasser : “The Challenge between brothers” | 1974, East against West!

“Against ourselves”: Hamburg: June 22, 1974.

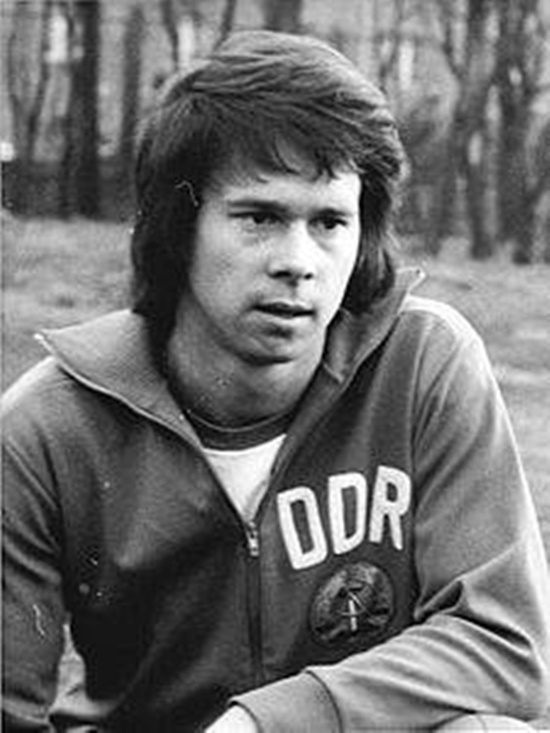

Jokingly, Sparwasser had stated that if the epitaph on his nameless grave were simply written with the words “Hamburg, June 22, 1974″, everyone would know who was buried. there”!! !

It refers to the match that took place as part of the first group stage of the World Cup in 1974, when West Germany, FRG, played East Germany, GDR, for the first and only time at international level during the 41-year period , at a time when the country was divided between the capitalist West and the communist East. In those times of great tensions during the “cold war”, embodied by the scars of barbed wire and the long concrete wall that crossed the former capital of the country, football acted as a connecting bridge for many points in the eastern part. Whenever a team from the other side of the divide visited an Eastern Bloc country for a European event, there was a collective clamor for tickets. It was not the kind of collectivist movement desired by the authorities in the East, but it illustrated a desire to see the stars from the other side of the political divide, as well as an enduring sense of belonging, a bond that remained strong if contained by the edifice of a the wall.

Even in the 1950s, it was not particularly unusual for clubs from either side of the divide to play friendly matches. It was a way to maintain some measure of contact with the divided country. Indeed, it was almost considered a play-off by all of Germany in 1956, when Kaiserslautern, who had been West German champions in 1951 and 1953, also finishing as runners-up the following two years, played against Wismut Karl-Marx-Stadt, the current champions of East Germany. The match was played at the Zentralstadion in Leipzig, and attracted massive interest with more than half a million applications made for tickets, exceeding the supply many times over. The people who were lucky enough to attend saw the team from the west triumph with two goals difference of a “score” of 5-3! In all the club matches between the German teams from the East and the West, it was usually seen how the latter always came out victorious.

The authorities in the East in the past would no doubt have liked to trumpet the success of the communist system over the corrupt capitalist West, but the reality was that teams from the GDR were usually a bit weaker. As the Cold War grew in the 1960s, the opportunity to hold such matches diminished. At least the teams from the East were no longer losing, but when the draw was made for the 1974 World Cup finals, chance – or fate, depending on preference – provided an opportunity for the national teams to play against each other, or so the German press wrote of the time: “We against ourselves”.

Now yes, there was more than just a club’s pride at stake. If the East German team were to advance, it would be a moment to paint the result as a great merit for the state and an important victory for the socialist system. The draw for the 1974 World Cup finals was made in Frankfurt on January 5 of that year. There were four groups, with West Germany as hosts in Group One and the other previous winners, Brazil, Uruguay and Italy, topping the other three groups.

The division of teams to fill each of the remaining places in the groups was entrusted to the innocent hand of a young boy chosen from the Berlin Schöneberger Sängerknaben boys’ choir. Call it what you will, irony, divine intervention, or just a game of randomly given cards, but the young man from the same city divided between the West and the East first provoked surprise, and then applause, after he pulled out the sign that said: “a 90-minute reunion of Germany on the football field, separated only by white and not red lines and a concrete wall” !!! As the host country, West Germany did not need to go through a difficult qualification campaign, but for the East Germans, who were in a group that included Romania, Finland and our Albania, they needed a little effort and luck before they took their place in the World Cup finals alongside the best representatives of the time in football.

Despite the fact that the first place in the group was headed by both rivals GDR and Romania in alternation, where both teams won against each other respectively the matches in their fields, only when the Bucharest giants came out with a 1-1 draw in Finland , the East Germans could qualify after winning all the remaining matches. Next to the two Germans in the first group were Chile and Australia, and while the draw that was set certainly predicted the drama in the final match of the group that would be between the Germans and the brothers of their separate. Before the start of the tournament, exactly one month before, the East Germans seemed to give a warning about what would happen in the challenge between them and the Westerners, precisely that perhaps their football was reaching a high level when the club “FC Magdeburg”, under brilliant coach Heinz Krügel, won the Cup Winners’ Cup, becoming the first and last East German club to lift a major European trophy. However, the clubs in the western part of Germany had no difficulties, as “Bayern Munich” lifted the Champions Cup only a few days after the triumph of “FC Magdeburg”. Even the players of “Bayern” would continue to hold this prestigious trophy of clubs in Europe for the next two years. It was the time when Cruyff’s “FCAjax” Amsterdam and Beckenbauer’s “Bayern” dominated the European club scene.

The first group matches started positively for both German teams. A sensational opener saw West Germany beat Chile 1-0 thanks to a Paul Breitner strike, while Georg Buschner’s East Germany secured a 2-0 win over Australia thanks to an own goal and a strike from Joachim Streich. “Hansa Rostock” team. After a not-so-easy first game, and with the points “in the pocket”, veteran coach Helmut Schön would see his West German team overcome Australia with ease. Three goals from Wolfgang Overath, Bernhard Cullmann and Gerd Müller were more than enough to testify to their strength.

The hosts were clearly finding their stride. At the same time, for East Germany, the going was somewhat more difficult. In a tense game against the South Americans in Chile, Magdeburg striker Martin Hoffman gave them the lead after 55 minutes, but Sergio Ahumada’s equalizer with 20 minutes remaining began to put the Chilean dreams on hold – at least for a while. In those times, not entirely without mischief anyway, the last matches of the group were not played simultaneously, that is, at the same time.

It was an arrangement that FIFA decided to approve later just after another last game in the group……and look how ironically again in the group that West Germany was part of in v. 1982 in the World Cup in Spain, the challenge which “left a bad smell” of cooperation in the air. The defeat of Germany against Algeria, together with them also qualified Austria of Prohaska, Shakner and that excellent generation of that representative force whose strength was also recognized by our national team. But that’s another story…… In the 1974 tournament, however, Chile faced Australia three hours or so before the all-German “brawl”, and a 0-0 draw meant that neither could qualify. now neither Chile nor Australia. All that was left to decide was who would win the group now and which regime would be able to claim sporting hegemony for their particular doctrine.

The game, which has been discussed in as much political as sporting circles since the choir boy’s hand drew East Germany’s draw in January, took place on 22 June. It was five months of waiting, anxiety and fear to be played in 90 minutes of football. As well as the inevitable political attention, it is important to note that on both sides of the border, there was also a great deal of public interest, not so much in promoting any particular political philosophy, but rather as a touch point, a link, between the divided people of a country or more precisely, the divided peoples of this country. It would not be surprising that a number of people living in the East were eager to see West Germany triumph. Both teams were seen as representing one Germany, so there was little or no national rivalry, and a result on the other hand would only strengthen an unpopular regime eager to build its fame by exploiting the sport, no matter how it was played. won, as subsequent events in a number of other sports would reveal the true path to success.

In the opinion of most pundits, the West German team was seen as the most accomplished and likely to prevail. This was not simply due to the performances of the two teams in the tournament so far. Nor was it because coach Schön’s team were reigning European champions (1972 they had convincingly beaten BS in the final 3-0), and any home advantage they held would be questionable at best. The main factor was that they were perceived to have the best players, the core of their team being taken from Bayern who had beaten Atlético Madrid in the final of the European Champions Cup. Yes, the Westerners were overwhelming favorites to win the match and top the group. However, it was not thought that their opponents, the easterners, would give up easily. In addition to FC Magdeburg’s European success, as I mentioned above, East Germany had won bronze medals at the 1972 Olympic Games and two years after this challenge to the West would take the gold medals in Montreal in 1976.

Although any direct evidence is hard to come by, a number of reports surrounding the game suggest that confidence was high for the West German side, with a comfortable certainty of victory the dominant feature. There would also be a fan lead for West Germany at the Volksparkstadion in Hamburg. Over 60,000 would watch the game, but of that number, only 1,500 selected guests from the East would be allowed to travel across the border to watch the challenge. It is also difficult to say that from that number all of them were staunch supporters of the regime. It should also be mentioned that the West German team had an extra incentive to win the match.

The veteran coach Schön, who was leading the western team for the third time in the World Cup, was born in the East German city of Dresden, although at the time of his birth, in 1915, the division of the country was not even thought of and was a event that would happen far in history. Much later, his family had left the East to escape the Soviet-imposed regime. Therefore, there was a strong feeling among the group that they were playing for Schön, literally and metaphorically. It was a theme captain Franz Beckenbauer used to spur on his teammates.

It is interesting to note that immediately after the opening ceremony, as the players were taking off their warm-up shirts, chants of “Deutschland, Deutschland” could be heard around the stadium. Was this just for the home team or some sort of statement from the people attending? The field had a running track around it, creating a space between the players and the spectators, but the excitement flowed down the steps of the audience and fell on the boys of the two teams on the field representing the divided country.

Uruguayan referee Ramón Barreto blew the whistle to start the game. Müller hit the first ball to Overath and the game is now in development. Soon, it became clear that the emotion in the air was one of tension. The desire to win from both sides was palpable, so was an assessment of the pressure exerted on the 22 players on the field, each seen to represent an entire doctrine of life as well as a nation. It wasn’t quite the Cold War involved in a football match, but still close to it.

With the all-encompassing political backdrop, no one wanted to make a mistake and caution was the watchword. Interferences were tempered and tempers controlled as a mutual respect—and perhaps a measure of brotherly understanding of each other’s situation—emerged. It was understandable, but it meant that the first part of the game became quite sterile. Heinz Flohe’s shot from the right flew wide of Jürgen Croy’s right post. The goalkeeper jumped towards the ball, but it was more of a gesture than a required save. The western side’s best chance of the half came when a clever pass from Beckenbauer to Müller allowed “Der Bomber” to round his defender before crossing it further into the area to Jurgen Grabowski and the ball deflected off a despairing throw. of Croy, who tried to catch it, but the ball went behind the big body of the Eintracht Frankfurt player, hitting just below where the two posts meet on the right of the east goal. Midway through the first half, Breitner shot high on goal as West Germany’s efforts continued to be broken by solid East defense giving their keeper Croy safety. Despite the persistence of the Westerners, it would be wrong to say that there was no threat from the opposing Eastern team.

Here’s a shot from the left of Lothar Kurbjuweit on goal that caused concern. Sepp Maier pulled towards the near post, Cullmann followed suit, leaving Hans-Jürgen Kreische quite free. Lauck crossed the ball into the area, which he placed between the goalkeeper and the defender, describing the entire rest of the goal as unprotected. In a 14-year career, Kreische would play over 250 league games for Dynamo Dresden, scoring almost 150 goals. In his club colours, this clean scoring chance would surely have been accepted, but in a match and with this pressure it would be completely different. As the ball reached him on the six-yard line from goal, Kreische bent and his shot ended up over the crossbar. The pure case had come and gone at the same time. The striker turned with his head down to receive a comforting gesture from Jürgen Sparwasser. This is how the first half ends without goals 0-0 and with one clean chance for each of the two Germanys. German – The West had clearly been the more dominant team, but as is often the case, the better chance fell to their opponents. For different reasons, both coaches would have had reason to feel both frustrated and relieved by the result.

The second half began as the first had ended. One difference, however, was that, for some reason, Maier had found it necessary to change his goalkeeper jersey from black to green. Everything else remained the same. West Germany continued to push forward and a ball from Müller set Grabowski free, but his shot was high, wide of the goal and not at all pretty. Such strikes in the stratosphere were becoming the order of the day. So with East Germany’s sporadic efforts and West Germany’s coming up against a solid blue wall of defenders to block any attempt at goal, a draw began to look increasingly inevitable. Given the other group results, it means that West Germany would top the group; the authorities in East Berlin would have to console themselves with an honorable retreat and progress to the next stage.

There was still time for that scenario to change. An effort from Breitner that at least looked on target, the ball bounced a few times before ending up in the arms of Croy. With 65 minutes played some tired legs started to show. Coach Buschner withdrew midfielder Harald Irmscher, replacing him with Erich Hamann. Many minutes later, the move would be extremely significant. On the other bench, Schön was also looking at the options. A few minutes later, he removed tough centre-back Hans-Georg Schwarzenbeck, who often provided stability at the back for Beckenbauer to complement his forward forays into attack, moves for both Die Mannschaft and Bayern, and fielding Horst-Dieter Höttges. Hoettges?

Yes! The well-known defender even among Albanian sports fans, who was “maddened” by our attacker, the excellent Panajot Panon, in the dramatic match in Tirana (0-0), which brought the elimination of the West Germans from the 1968 European Championship.

Schoen also removes Overath and boosts the drive when he brings on Günter Netzer. For the next few minutes, nothing changed, until the remaining 13 minutes towards the end. With his back to goal, Uli Hoeneß stopped the ball with a header in an attempt to set up a forward-footed shot, but the ball fell calmly to Croy.

The latter, looking quickly at his teammates, spotted the fresh legs of Hamann, who had just entered the game, who had jumped forward on the counterattack on the right wing, and threw the ball to him. The 30-year-old was playing in the only of three games in which he represented his country but, in the next few seconds, he was to take a leading role in one of East Germany’s greatest sporting triumphs. Moving forward, he raised his head after entering the Westerners’ half.

Sparwasser for his part was accelerating into a space as the Western defense was closing down. Hamann crossed a perfect ball to complete his run as well. Sparwasser eluded the cover of a sliding Beckenbauer, entered the area, then fired the ball into the air and past Maier’s right foot to give East Germany the lead. 1-0! Easterners celebrate, stunned Westerners keep their hands on their hips. In fact, they had not seriously threatened to score except for the case mentioned in the first half by Müller for Grabowski who had not been able to take full advantage. As time went on, a draw that would see them top the group looked an increasingly inevitable conclusion to the game, but their lethargy in sharing “a share of the spoils” had betrayed them to their brethren hungry.

Now they had “a mountain” to climb – and precious little time to do it. Inevitably, the pressure increased on the Westerner, now taking a series of free kicks and corners but without much brilliance, clarity and accuracy. So hardly any serious threat in Croy’s goal. The German-Easterners closed back and held a strong center line. When the final whistle sounded, it was the East Germans in blue shirts who were surrounded by photographers each wanting to capture their moment of triumph with Croy and Sparwasser taking special credit.

Jurgen Sparwasser, the author of the goal for the East in the only challenge between the two divided Germanys during the “Cold War”

The Magdeburg striker was aware of the importance of the scored goal, stating later (even with a bit of humor) : “If one day my tombstone simply says ‘Hamburg 74’, everyone will know who lies beneath.” In East Berlin, the authorities would be overjoyed. In the cities and suburbs of East Germany, people were less so. The East had triumphed over the West. Socialism had defeated capitalism. Fifteen thousand fans celebrated while 58,000 left from east to west. But what did that mean?

The win took East Germany to the top of the group. Normally, this would mean an easier path to progress, but as things have changed, this was not the case. Drawn into a second-stage group alongside Brazil, Argentina and the Johan Cruyff-inspired Netherlands, a single point was all they could muster for the easterners after a pointless draw in the last game against Argentina, when both the teams were already eliminated. In contrast, the West Germans faced Sweden, Poland and Yugoslavia, duly winning all their matches and then defeating the Dutch in the final. If the East had won a battle, the West would have won the war. It was a political triumph to savor, but perhaps this was also a Pyrrhic victory. Later, the players wearing the GDR jersey that summer evening would seek to downplay any political significance.

Tall, powerful and blond, every inch the athletic sweeper that was East German captain Bernd Bransch, would show that it was the victory that mattered, not the opponent over whom it was won. Goalkeeper hero Jürgen Croy would admit that, “It was important because it was the World Cup and because it was Germany against Germany,” but added, “Of course it was praised by the politicians, but it happens everywhere. All countries try to take advantage of political success in sport.” Let’s leave the final summary to Jürgen Sparwasser, the goal-scoring hero. When asked about how his life changed in the East, he said: “According to the rumors, I was rewarded a lot for this achievement, with a car and a prize money. But this is not true before the fall of the Berlin Wall, 40-year-old Jürgen Sparwasser left for the West.For a short while, it looked as though the Euro 92 qualifiers might produce a repeat of that June evening in Hamburg 1974 when the two Germanys withdrew from draw again to play with each other. Political events overshadowed things, although the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 precluded any such events. On 12 September 1990, the “Deutsches Demokratisches Republik” – East German Democratic Republic – played its last international match: a friendly against Belgium at the Anderlecht Astrid Parc Stadium in Brussels. Less than a month later, the two separated sectors of Germany were reunited. The war between the brothers ended.

WATCH THE MATCH HERE BELOW:

1-st Half

_____________

2-nd Half

© By Pjerin B. – August 2021

________________

Sports Vision + / The Hour of Champions since 2013

Follow us:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/VizionSportiv

Dailymotion: https://www.dailymotion.com/kinetografiashqiptareartisporti

Blog: https://pierosportvision.blogspot.com/

Discover more from Sports Vision +

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.