Blood and Brutality: The Infamous 1962 World Cup Clash!

Fists, Feet, and Fury: The Challenge the remains the most violent match in World Cup history!

We will now travel back in time, to Chile, to the 7th edition of the 1962 World Cup.

The 1962 FIFA World Cup in Chile will forever be remembered for one match that embodied the darkest aspects of human nature. The clash between Chile and Italy on June 2, 1962, was more than just a football match – it was a brutal, violent, and chaotic spectacle that shocked the world.

Two teams, fueled by national pride and a desire to win, took to the pitch with a ferocity that would leave a lasting scar on the beautiful game.

The strongest and perhaps best-known criticism of the game came from BBC’s David Coleman, who introduced the match as follows:

“The game you are about to see is the most stupid, appalling, disgusting and disgraceful exhibition of football in the history of the game. This is the first time these countries have met; we hope it will be the last. The national motto of Chile reads, ‘By Reason or By Force’. Today, the Chileans weren’t prepared to be reasonable, the Italians only used force, and the result was a disaster for the World Cup.”

1.

The 4th edition of the World Cup after World War II is on the horizon. Football has increasingly gained great interest among the masses of people in various countries around the world, becoming one of the most followed sports, and sometimes even by groups of fanatics, even exceeding the limit of being a sport!

The 1954 and 1958 tournaments had both been held in Europe. If this trend continued, South American nations threatened to boycott the tournament – as they had in 1938, so their respective federations insisted that the 1962 tournament would be held on the Latin American continent at all costs.

Most assumed that Argentina would be the choice, but the Chilean federation put forward its own candidacy.

At the FIFA congress in Lisbon on 10 June 1956, Raul Colombo, the man presenting the Argentine candidacy, said “We can start the World Cup tomorrow. We have it all.”! However, the Chilean football federation, represented by Carlos Dittborn and Pinto Duran, gave four arguments in defense of Chile’s candidacy. They regularly and continuously participated in conferences and tournaments organized by FIFA!

In addition, Dittborn mentioned Article 2 of the FIFA statutes, which dealt with the role of the tournament in promoting sports in countries considered “underdeveloped”.

In a counterpoint to Colombo’s claim that “We have it all”, Dittborn coined the phrase “Because we have nothing, we want to do it all” (Porque no tenemos nada, queremos hacerlo todo).

After a speech lasting about 15 minutes, the Chilean candidacy won the World Cup with 32 votes to Argentina’s 10, with 14 abstentions.

The first hurdle had been jumped, leaving Chile with the rather more daunting task of building up the infrastructure needed for a World Cup. Roads, stadiums and transport would all need to be improved. There was little time to waste.

With great diligence, plans were drawn up to prepare the host country.

But on May 22, 1960, the Valdivia earthquake struck Chile, the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in human history, devastating Chile. Thousands died, and many more were forced to flee their homes. For a country already struggling with a poor economy, the cost of the earthquake was estimated at $6 billion.

Four of Chile’s eight intended venues were left unusable. Support poured in from around the world, and efforts were made to save Chile’s World Cup.

Two cities managed to repair their stadiums in time for the 1962 games, bringing the number of venues to six. Braden, an American copper company based in Chile, also donated their undamaged stadium in Rancagua for the games. Seven venues would suffice.

2.

The World Cup was to be held from May 30 to June 17, 1962, with the participation of 16 finalist teams divided into four groups of four teams each.

At the beginning of the 60s, Italy experienced an explosion of economic development that excited the country, revealing itself to the world as an industrial country on the path of a radical transformation. Football in Italy would also face new times of this transformation.

Such a change was all the more necessary given the unsuccessful participation of the “azzurri” in the two editions of 1954 and 1958.

Italy, twice world champions until that 7th edition (1934, 1938), had in its composition quality players and the hope of doing well was widespread. An Italy that had Maschio, Angelillo, Altafini, Corso, Rivera and above all the star of the team Omar Sivorin, the player who had given Juventus, three “scudetti” in the last four years.

However, the “Azzurri” led by coaches Giovanni Ferrari and the president of Spal, Paulo Mazza, had not an easy time in the qualifying match against Israel. From an incredible 0-2 deficit, with just 11 minutes left in the match, the Italians managed to defeat Israel in Tel-Aviv 4-2!

It would be precisely Sivori who would score four goals in the return match in Turin where Italy would win 6-0, booking their ticket to the finals in distant Chile!

Chile in the 1960s was a country trying to leave behind the trauma of a catastrophic earthquake, the traces of which were still evidence of that phenomenon that had brought great damage to the life of the country which itself was going through a period of relatively high inflation with mild fiscal deficits. The persistent inflation in the 1960s was, as in previous periods of Chilean history, closely linked to fiscal deficits and wage indexation.

Meanwhile, the Chilean football team was participating in the World Cup for the third time. In 1930, it had finished 5th, and in 1950, 9th. It had withdrawn in two editions, those of 1934 and 1938, and had failed to qualify in 1954 and 1958.

The Chilean National Football Championship, which had ended its 30th edition in 1962, was not distinguished by any level of quality compared to other American or European leagues.

The most famous clubs in the country, the base of the players of the national team, were Colo-Colo, Universidad Catholica, Universidad de Chile, the latter the reigning champion, the team that had scored 100 goals during the last championship (1962).

The match between Italy and Chile, scheduled for June 2 in Santiago, would be the second of Group “B” which included West Germany and Switzerland.

“We will win against Switzerland, at least by two goals,” Chilean footballer Sanchez would declare before the match. And so it happened, it was even Sanchez himself who scored two goals in which the organizers had won their debut match (3-1) against Switzerland, while the Italians were coming off a 0-0 draw against title contenders, FRG!

Although it was considered a valuable point, immediately after the match, controversy arose among the Italian team staff regarding the starting lineup.

The match between Italy and Chile would be unstable from the start, even before the green battlefield began.

A pair of Italian journalists – Antonio Ghiredelli and Corrado Pizzinelli – send a report to Europe stating:

“Chile is a poor country, but quite proud.

The telephone does not work, and taxi drivers are as few in circulation as faithful husbands. A cablegram with Europe costs too much, while a letter by air would take 5 days to reach its destination. In many neighborhoods of Santiago, street prostitution is practiced openly. From the point of view of economic development, Chile can be compared with the countries of Africa and Asia”.

The way the Chilean capital was described was unfavorable, which had a significant impact on the climate of the scheduled match between Chile and Italy.

What appeared in the Italian media made Santiago look like a Latin “Gomorrah” full of crime and debauched women. Needless to say, the Chileans did not respond well to this unpleasant situation, showing hatred.

The two Italian journalists ended up leaving the country before the match started. An Argentine journalist, who got mixed up with one of the Italians in a bar, was beaten by angry Chileans.

In addition to problems of this nature for the Italian representative, there was also a controversy over the formation between the technical staff and a group of journalists. Setting the starting lineup for the match against Chile is a conundrum solved in an atmosphere worthy of a conspiracy.

3.

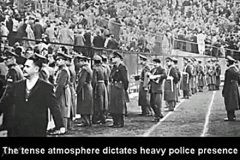

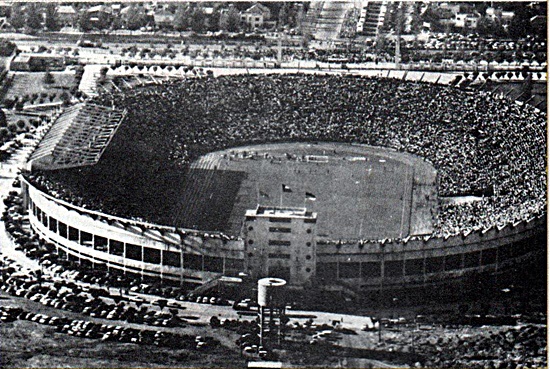

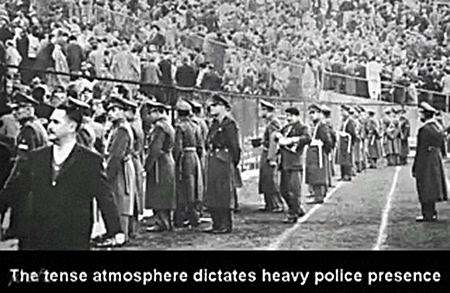

On the eve of the match between the hosts and Italy, tension is at an all-time high. 66,000 crazed fans have packed Santiago’s Nacional stadium as Italy and Chile march onto the field of battle.

The Italian team were under no illusions on 2 June when they lined up against Chile. They knew they were in for trouble.

Italians had been banned from Chilean bars and the Azzurri players were subjected to heckling from the local populace.

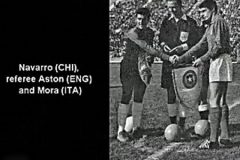

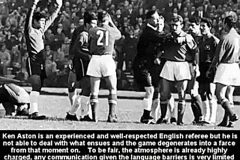

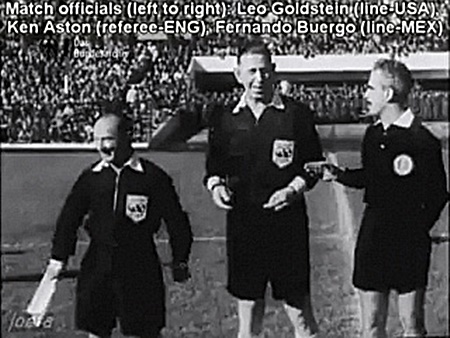

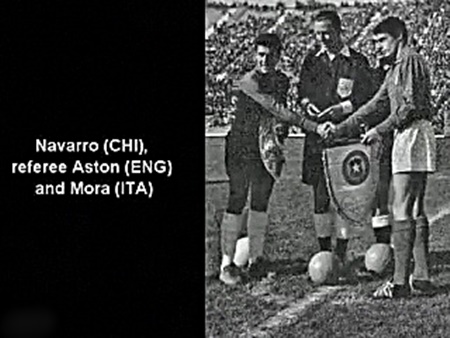

The Azzurri in their traditional blue shirts and white shorts. Chile took to the field in their all-red uniform. The referee was Englishman Ken Aston, who actually let go of a bit more control over the match.

The tension in the stadium was palpable. The Chilean fans appeared hostile, as if they had pointed their guns at the Italian players or were simply waiting to find an Italian in the stands to vent their anger.

Hoping desperately to placate their hosts before the game, Italian players ran to all corners of the stadium prior to kickoff handing bouquets of flowers to Chilean women in the crowd. The flowers were promptly thrown back to the players in disdain. This day there would be no reconciliation.

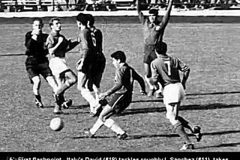

The game has started and referee Aston blows his whistle for the first foul after 12 seconds. Within five minutes Aston has to intervene to prevent a possible fight between the two teams.

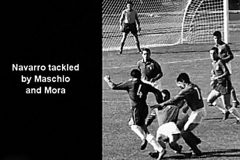

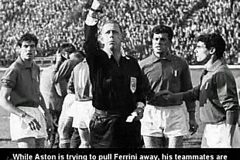

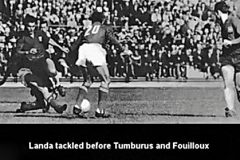

In the 12th minute, Giorgio Ferrini responded to what he thought was a deliberate foul by Honorino Landa by giving the Chilean a kick in his direction right in front of the referee. Aston sends him off and Ferrini goes crazy. Ferrini refused to leave the pitch.

The Italian wanted to know why Landa hadn’t been booked for continually fouling the Italian, and for the next eight minutes, Ferrini remained on the pitch demanding justice.

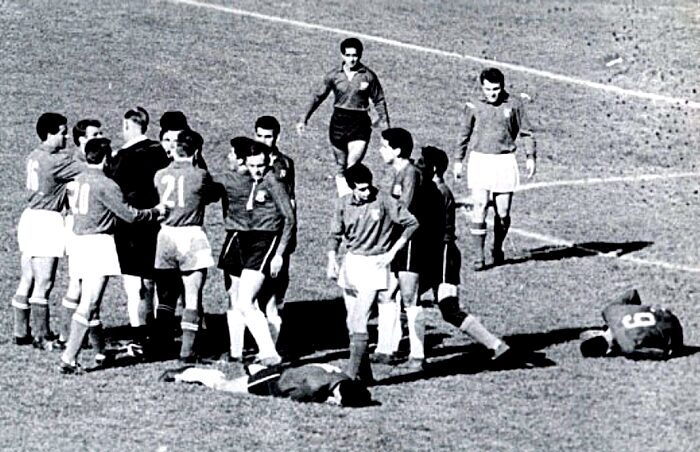

Amid hisses and boos from the crowd, Ferrini stood his ground, growing ever more defiant. Eventually a squad of Chilean policemen forcibly removed him from the field.

Very quickly the game turns into an anarchy. Shortly before half-time, Chilean winger, Leonel Sánchez, went down following a late tackle from Mario David.

The son of a professional boxer, Sánchez was no stranger to physicality and promptly responded to David’s tackle by delivering a left hook to the Italian defender’s cranium. Perhaps forgetting he was commenting on football and not boxing, a BBC pundit remarked, “I say, that was one of the neatest left hooks I’ve ever seen.”

Despite being yards away from the linesman, Sánchez escaped a booking but he wouldn’t escape David.

Minutes later David returned the favour to the Chilean with a flying boot to the head in front of an astonished Aston. Aston dutifully sent David from the field of play leaving the Azzurri with nine men.

Several more times in the second half, Chilean police were forced to intervene to maintain a relative peace during the game.

At times the match resembled rugby, other times boxing, yet seldom did it resemble football.

Midway through the second half Sánchez yet again managed to escape the referee’s book when he punched Humberto Maschio following a nasty clash between the two.

Reflecting afterwards on the match, Aston decried: “I wasn’t reffing a football match, I was acting as an umpire in military manoeuvres.”

Few could disagree.

The Italians had begun to crumble and, with 73 minutes on the board, Chile notched the game’s first goal when Jaime Ramírez headed the ball in from short-range.

Three minutes later Jorge Toro doubled Chile’s lead with a spectacular long-range effort.

When Aston put an end to the game the Italians scuttled from the field, fearful that the crowd or even worse, the Chilean squad, would get their hands on them.

Forget the two points, the Chileans wanted blood and revenge for the articles written by the two Italian journalists, and in addition to the victory, they also got revenge.

Remarkably the following morning two different sets of match reports emerged.

In Chilean publications, the Italians were blamed for instigating the violence amid claims that the Chilean national team were only defending themselves.

Jorge Pica, a Chilean FA representative, even went so far as to accuse the Italians of doping prior to the game.

Pica told Chilean journalists:

“They seemed to go on the field only with the intention of injuring the Chileans … it was like a rodeo. Frankly, I think they were doped. Now I can see the necessity for laboratory tests on players after matches.”

The Italian response was equally emotive.

Official complaints were passed on to FIFA about Aston’s “biased” performance alongside claims that the Chileans acted like cannibals on the field of play.

When word reached Italy about what had happened, the Italian army had to be called in to protect the Chilean consulate in Rome.

In England, media outlets viewed the match as an embarrassment to football. The Mirror warned that the World Cup was heading for disgrace if matters weren’t cleaned up. The Express labelled the game a bloodbath.

Calls were made for FIFA to step in, but sadly the governing body’s reaction left much to be desired. Despite assuring referees that the strongest possible examples would be made of the Chilean and Italian sides, FIFA suspended Ferrini for only one game with Sánchez and David escaping punishment altogether.

Attempts were made to draw a line in the sand and just continue with the tournament.

The Battle of Santiago, as it became known, was one of the most senseless, violent matches in World Cup history and sparked a decade of high-tempered games between European and South American teams.

It had set a tone for the rest of the tournament, and it wouldn’t be long before the next controversy reared its head.

Even from the first matches, it was clear that a torrent of scandals would erupt in the stadium.

“A field transformed into a ring” – that’s how a commentator would call the match between Italy and West Germany, where football was often combined with boxing.

The Spanish continued the boxing battle in the match against the Czechoslovak players. The Austrian referee Steiner was forced to stop the match for about five minutes.

After the first matches, where kicks and punches were more or less seen and several footballers were injured, FIFA drew the attention of the referees, who should be stricter and not be liberal towards those who provoke serious play.

But the violent games continued, as happened in the Yugoslavia – Uruguay match, where both sides tried to combine boxing with football. Only after the Czech referee Galba expelled Cabrera and Popovich from the field, the game began to flow into the football channel and its rules as a sport, for which the World Cup was being held.

In the following days, more violent matches took place, including a match between Brazil and Spain that was interrupted by a pitch invasion and a match between Hungary and Bulgaria that saw a Hungarian player kicked in the head.

The leitmotif of the Argentina – Bulgaria match was the whistle of the Spanish referee Gardeasabal. The Argentines proved that in addition to football they also know how to do freestyle wrestling.

In the next match the Soviet Union – Yugoslavia there were more kicks than football

The 1962 World Cup was a turning point for football. It marked the beginning of a new era of increased competitiveness and physicality in the sport.

Five days after the Battle of Santiago, a withered Italian side beat Switzerland 3-0 in a dead rubber game. The Italians already knew they had been eliminated from the tournament and, battered and bruised, they returned home vowing revenge. Chile and West Germany had made it through to the later stages at the expense of the Azzurri.

Although Chile eventually made it to the semi-finals, few European observers cheered them on. For the remainder of the tournament, the Chilean side were view with suspicion by European outlets.

A schism had emerged between European and South American states.

The following season, in 1963, Pelé’s Santos travelled to the San Siro to face off against Nereo Rocco’s AC Milan in the Intercontinental Cup.

Many hoped matters had been forgiven but right from the kick-off, it became clear that European sentiment of South American sides had not improved with time.

Players from both sides began to weigh in with sly punches, late tackles and on two occasions, kicks to the head.

When Milan travelled to Santos for the return leg, the Brazilians physical response nearly caused the Milan players to leave the field of play.

The gauntlet had been thrown down between European and South American sides and thus, began a decade of ill-tempered affairs between the two continents that flared up in a series of World Cup and Intercontinental Cup matches.

The following years would see Alf Ramsey describe Argentina as “a pack of animals”, Pelé lament the physicality of the Europeans, and matches in the Intercontinental Cup that left players bruised, bloodied and at times unconscious.

Looking back at the Battle of Santiago and its impact on European and South American relations, one is left pondering what would have happened had Antonio Ghirelli and Corrado Pizzinelli kept their opinions to themselves.

The Battle of Santiago was a symbol of this shift, a clash between two teams with different styles and cultures that ended in chaos and violence.

Despite the controversy surrounding the match, it remains an important part of football history, a reminder of the passion and intensity that defines the sport.

The match may have been a dark day for football, but it also marked the beginning of a new era for the sport, one that would be defined by increased competitiveness, physicality, and passion.

The legacy of the Battle of Santiago continues to be felt in football today, a reminder of the power of the sport to inspire and to infuriate.

In conclusion, the Battle between Chile and Italy in 1962 was a pivotal moment in the history of the World Cup, marking a turning point in the sport’s development.

The match’s violence and controversy shocked the world, leading to changes in the way the game was refereed and players were disciplined.

However, the legacy of the Battle of Santiago goes beyond the sport itself. It represents a clash of cultures and styles, a symbol of the tensions and conflicts that can arise when different nations and ideologies come together. Today, that violent match remains an important part of football history, a reminder of the power of the sport to inspire and to infuriate.

It serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of violence and aggression in sport, and the importance of fair play and respect for opponents.

In the end, the Battle of Santiago was a defining moment in the history of the World Cup, one that continues to shape the sport today.

June 2, 1962 | Estadio National de Santiago

2-nd match of “B” Group for the World Cup

Chile – Italy 2-0

Ramirez 73`

Toro 87`

Referee: Kenneth Ashton (Eng.)

Linesmen: Leo Goldstein (Israel) / Fernando Buergo Elcuaz (Mexico)

Attendance: 66.057

Red cards: Ferrini 8` ; David 41`

Chile: Escuti-Eyzaguirre, Contreras, Raul Sanchez, Navarro (cap)-Toro, Rojas, Ramirez, Landa-Fouilloux, Leonel Sanchez

Coach: Fernadno Reira

Italy: Mattrel-David, Janich, Salvatore, Robotti-Tumburus, Ferrini, Mora (cap), Altafini-Maschio, Menichelli.

Coach: Paulo Mazza

By: Pjerin Bj

New York: December 9-11, 2024

© Reserved Material

________________________

Sports Vision + Plus / Champions Hour in activity since 2013

Discover more from Sports Vision +

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.