1973, Chile – CCCP! | The phantom match and the ghosts of the Santiago Stadium in Chile!

In 1973, the Soviet Union and Chile would meet to determine who would be the team that would go to the 1974 World Cup finals in West Germany.

On the face of it, it was just a football match. Beneath the surface, there was a military coup, the Cold War, and a stadium being used as a detention center. It was a football match that should never have been played.

1.

Dear Don Pablo Neruda, I allow myself to address you in this somewhat colloquial and perhaps irreverent way, to cancel the distance that has caused me pain for too long. My name is Francisco Valdés, I turned 50 the day before yesterday, I have a wife and a son whom I named Pablo, like you. I work as a clerk in a bank in Santiago and I earn quite well. I am writing to you to take a huge weight off my conscience. I have been carrying it inside me for almost twenty years.

It was November 21, 1973. It is not easy to believe in ghosts, and I do not know who among you believes in them. Go ahead and look for an answer, but before you give it, wait until the end of this story because perhaps you too, when you have listened to what we are about to tell, might realize that there are places where the past does not pass and presences hover.

Places where there is something beyond what we see. And this beyond, this line to cross, is not necessarily the border between life and death. Because the first of the incredible things is that these places suspended between present and presences can also be rectangular fields surrounded by stands. Even football stadiums can be inhabited by ghosts. And there is one stadium in particular where presences hover and the past never passes.

This is the National Stadium in Santiago, Chile.

Dear Don Pablo Neruda, on that November 21, 1973, the Chile-Soviet Union soccer match was scheduled at the National Stadium in Santiago.

A play-off to go to the World Cup in West Germany the following year. I was the captain of Chile and wore the number 6 jersey. In the first leg we had drawn 0-0, a good result. In the return leg we were counting on winning with the help of our fans. Yes, the fans.

In reality, this is a story with no middle ground. There is no room for spectators. You are either the executioner or the victim.

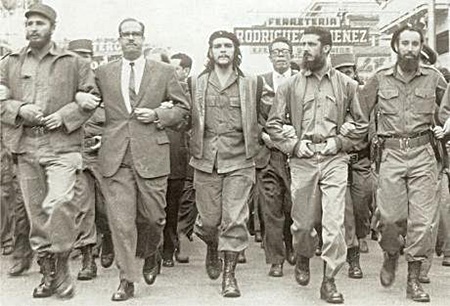

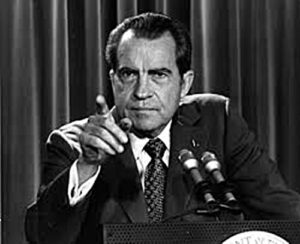

It all begins the day after the military coup organized by the United States of Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon that on September 11, 1973 overthrew President Salvatore Allende and imposed the military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet.

In the days of the coup, there were no fans in the stands of the Stadium in Santiago, Chile because the stands suddenly became a huge open-air prison. The locker rooms, the corridors and even the smallest room in the belly of the plant are transformed into a place of torture and elimination of political opponents. It is no longer a stadium. It is a concentration camp.

A real concentration camp.

But why is Chile subjected to so much violence?

It’s because Allende, president for three years, is a socialist and in Latin America in those years they write socialist but read Marxist.

To describe him, the photo taken in 1959 in Havana is enough.

The revolution has just brought Fidel Castro to power and he runs to Cuba where, in addition to Fidel, he embraces Ernesto Che Guevara. Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and Allende.

The photo that unites them and immortalizes them says everything about the president of Chile, this socialist who, unlike Fidel, came to power not thanks to a revolution but with democratic elections, those of 1970. A success that Allende will celebrate first with a military parade in Santiago, then with a speech at the National Stadium of Chile. In the stands, citizens and not fans. Allende looks at them but the Marxist president’s words are addressed more to the tenants upstairs than to them, those who consider themselves the administrators, or rather the owners of the condominium made up of the rich America of the North and the poorer one of the center-south.

Those gentlemen bear the names of Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, President and Secretary of State of the United States of America.

That day, at the National Stadium of Chile, more than a chorus, a cry is raised. The voice is that of President Allende. We are the legitimate heirs of the fathers of the country. Every people has the right to develop freely. Chile, which respects self-determination and practices non-intervention, can legitimately demand that any government act in the same way. Workers of the country, you and only you are the triumphants.

“Upstairs”, Nixon and Kissinger narrow their eyes in a mixture of anger and fear. They only have in their heads that Chile is a dangerous, very dangerous precedent, that could infect many countries in Latin America and that action must be taken now. The problem is that the Americans in Chile do not have a reliable alternative. And if you don’t have a backer, the millions of dollars you’re ready to put on the table to support, buy and bribe, this time might not be enough. The Liberal Party, on paper, might even do well and in the ’70 elections it collected more than a third of the voters.

Yes, this is a good basis, but the real problem is the Christian Democrats of Rodomiro Tomic, who in those same elections even risked running as allies of Allende. And this means that, in case of emergency, the left and the Christian Democrats could even join forces. Stop, let’s stop for a moment, just for a moment.

The 70s, Christian Democrats and Communists winking, it really seems like the Italy of Berlinguer and above all of Aldo Moro. Sometimes, to understand our history, even perhaps our political murders, it is necessary to know the stories of others. And so let’s start talking about Allende’s Chile, from which Washington has no way out.

For three years the American administration will do nothing but look for the time, place and best way to overthrow Allende and give the keys to the country to someone who is not a politician and who perhaps sports a military uniform. One day Roger Morris, at the time of the facts a member of the National Security Council of the United States, would explain. No one in the government realized how ideological Kissinger was on the problem of Chile.

No one realized that Kissinger considered Allende much more dangerous than Castro. Yes, Chile even more dangerous than…..

The attack comes on September 11, 1973. It is 7 in the morning when ships of the Chilean navy occupy the port of Valparaiso. Allende runs to the Palace of the Moneda, seat of the Presidency of the Republic. Air forces and tanks have already begun to radio and television. At 8:30, just an hour and a half after the start of operations, the armed forces declare that they have assumed full control of the country and ask Allende to resign.

The president, who is walking around with a helmet on his head in the rooms of a presidential palace that is about to be bombed by the air force, refuses and, through the Communist Party’s radio, Radio Magallanes, the only one still able to broadcast, shouts his political testament. These are my last words. I am certain that my sacrifice will not be in vain.

I am certain that, at the very least, there will be a moral lesson that will punish cowardice, and betrayal. Long live Chile! Long live the people! Long live the workers! Long live the people! Long live our workers!

At this point, the president grabs the gift that Fidel Castro gave him, perhaps, in that famous visit to Cuba in 1959. It is a Kalashnikov, the Soviet automatic rifle already used in the Second World War. Then, under the eyes of his personal doctor, Allende sits down, holds the butt of the gift and the rifle between his legs. Two shots are fired. At 65 years old, the president who did not want to resign in the face of the coup has taken his own life.

In the first afternoon it is already all over, but what is about to begin will not be less violent. In the very first days of the regime there are already hundreds and hundreds of victims of the military, among them also Viktor Hara, 41 years old, singer-songwriter, first seminarian and then communist militant. The coup surprises him in that university where the raids start immediately.

Immediately because the coup plotters realize the size of Allende’s popular support because there are no prisons large enough to contain all those who, in an instant, have become opponents. And so here are the stands of the National Stadium of Chile. Viktor Hara, together with the 600 arrested at the university, first passes through here, then is taken to a smaller structure, more or less a sports hall, also called by the name of Stadium of Chile. Here torture is not the same for everyone. Sadism always suggests different ways and for Viktor Hara the butt of a gun breaks the hands with which he plays the guitar.

He will die two or maybe three weeks after the coup. His wife will identify him among 70 other corpses. The body is that of a Christ, the Good Friday. He has trousers rolled up at the ankles. In his pocket his wife finds a note with the latest composition that can only be called so Chile Stadium.

There are 5,000 of us here. How many are we in total? There are 5,000 of us here. But how many are there in total in the cities of the whole country? Six of us are lost in stellar space. One dead, one hit. How could I have believed that a human being could be hit? The other four wanted to take away all their fears. One by jumping into the void, another by banging his head against a wall. But all with their gaze fixed on death. How frightening the face of fascism is. What a gap the beak of fascism causes. At this point it is useless to add other details about that violence. Maybe we have already said everything because evil is like the days of prison, always the same.

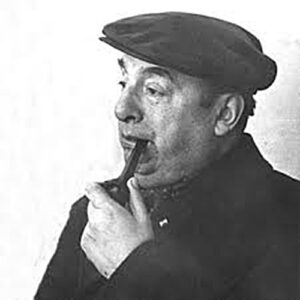

Evil does not renew itself, it is obsessive, repetitive, without imagination and so there is really no point in getting lost in other details. Two other things, however, need to be added. The first concerns a coincidence so incredible that for years many will continue to think that it was the regime and not prostate cancer that killed Pablo Neruda.

Yes, Pablo Neruda, the man who always knew how to look beyond and offer hope, died just 12 days after the coup, on September 23. Neruda, much more than a poet, much more than an intellectual, much more than a militant of that left that had even offered him the role of presidential candidate in 1970 which Neruda had refused because, poets can be very concrete, he knew that the right candidate was Salvador Allende.

Pablo Neruda, that poet whose words could have been one of the few anchors of freedom in the face of the violence of General Augusto Pinochet, leaves while Pinochet is still tightening the screws of the new regime.

And then there is another circumstance to mention from this Chilean September of 1973. While stadiums and sports halls become a place of torture, rape and murder, sports do not stop, especially football and, in particular, the national team. In the days of the coup, Roca, the red one, is in retreat to prepare for the first leg of the play-off that will assign the last place in the 1974 World Cup in Germany.

The appointment is in Moscow. Yes, it is incredible, but it is really so. The challenge will be between the capital of international communism and the country of what will reveal itself as one of the most bloody right-wing dictatorships of the entire twentieth century.

Meanwhile, on September 26, the country buries Pablo Neruda.

The funeral turns into the first anti-queen demonstration with the carabineros who, outside the stairs, follow the crowd that follows the coffin. In that funeral car, however, it is as if there was also the president who killed himself in the moneda and who could not be greeted by his people. The crowd knows it and, at a certain point, begins to invoke the name of Neruda next to that of Allende.

The tension can be cut with a knife. The rifles, however, are not taken up and, at the end of the day, there are only withered flowers, tears and a frightening feeling of loneliness.

At the same time, this long and narrow country between the ocean and the mountains, split vertically by violence and politics, this country so beautiful and so suffering, gathers together all its best players and entrusts them with the hoarse shirt, the red shirt of the national team, because in Moscow they have to play against the Soviets for the first leg of this incredible challenge. In the stands 60,000 spectators.

The two stars are the two center-forwards, Oleg Blokhin of Dynamo Kiev and Francisco Valdés of Colo Colo.

We have very few images of this tense and fragmented match. Even the photographs are rare. On the field, the Soviet Union shows technical and physical supremacy, but the goalkeeper, Juan Olivares, is unbeatable.

At the final whistle there are no goals. 0 – 0.

Everything will be decided in two months, when, in the return match, the USSR will visit Chile.

II

The days before the match were hell. The Soviet national team announced that it did not intend to come to play in Santiago in protest against the fascist coup of General Pinochet. Our leaders, at the suggestion of the International Federation, forced us to take the field anyway. There was Chile, the referee, an Austrian.

But there were no opponents in front. A unique case in the history of football.

On November 21, 1973, in Santiago, Chile, the return match of the play-off must be played to assign the last available place for the 1974 World Cup in Germany. The Soviet Union must arrive in Chile. The first leg ended 0-0.

But the last few weeks have been dramatic in Santiago. There was the coup d’état by General Augusto Pinochet, wanted, paid for and supported by the United States of Nixon and Kissinger. President Salvatore Allende, a socialist, rather than give up, shot himself in the head in his office. And then, just two weeks later, Pablo Neruda died. It was a tumor, but many will continue to think for years that it was the regime that got rid of him.

Pablo Neruda, the last anchor of freedom in the face of the violence of General Augusto Pinochet. In this climate, the challenge between the champions of communism and the country of the right-wing military dictatorship becomes impossible, also because it has been known throughout the world that the national stadium in Santiago, where the match is set, is precisely the stadium that was the scene of torture, murders and rapes.

For days and days this was an open-air prison, a concentration camp for opponents arrested immediately after the coup. The photos traveled because the first crack in power that believes itself omnipotent is the stupid pleasure of showing its own arrogance. At that point the Soviet federation, on the mandate of the general secretary of the Communist Party Leonid Brezhnev, inevitably and, let’s say it, since FIFA is silent, rightly asks to play in another stadium.

Because no one believes in ghosts, but here you can smell the strong smell of blood, here there are bullets planted in the walls, here, to have fun killing, they played Russian roulette with those poor people suddenly torn from their homes. In the National Stadium of Chile they threw the opponents into the void after having made them climb the stairs that lead to the top of the stands. And then playing here would be bordering on moral complicity.

Then the Soviets put the load of propaganda on top and this is useless to say because they too have a guilty conscience, but news and photos of the gulags where their opponents are concentrated and tortured have not gone around the world. But let’s stay at this stage because this is the history of Chile and not of the USSR and then, for goodness sake, playing there is really not possible. For the Chilean authorities, however, hosting here those who remain red even when they take off that damned t-shirt on which they have written CCCP in capital and Cyrillic letters is truly an irresistible whim because you will force them to run and attack among those that Pinochet considers the ghosts not of the opponents but of their idea of socialism that the Americans feared could infect all of Latin America.

And then, the cherry on top, even the Chileans watching the match on TV would have understood the full force of a regime that first tortures opponents in the stadium and then forces the Russians to play there as if nothing had happened. However, in October, the Soviets presented an official note to the International Federation to say that the national stadium of Chile is inadequate for the reasons you know.

The hot potato then passes to FIFA which orders an inspection. Now, we don’t know what the men of the world government of football saw or didn’t see .

It is possible that there were still prisoners inside the structure even if, probably, the structure has now been cleared and cleaned. But here the problem is not what the stadium is at this moment.

Here, what crushes the heart and mind is something that, like a ghost, is there but you don’t meet. The blood may have been scraped away but you can’t erase its weight with a coat of paint. FIFA, however, limits itself to the bureaucratic homework. It stops at the appearance of things because we know it. We know very well that FIFA doesn’t do politics but if thousands and thousands of people have passed through here and tens, perhaps hundreds of them have been killed what do we care if the measurements of the penalty area are precise to the centimeter? What do we care if there is electricity and if the spotlights are turned on like an art show? What do we care if the showers have hot water?

FIFA never gets involved in politics.

We know that but this is about humanity, about respect for the dead. It’s about looking, not just seeing.

But all this doesn’t happen. For the officials of the International Federation only the showers with hot water count, the spotlights with the bulbs and the size of the penalty area and the National Stadium of Santiago de Chile is up to standard and therefore suitable to host the World Cup play-off between Chile and CCCP.

At this point the Soviet Union decides not to leave for Santiago. The order, which I laugh at as a Pablo Neruda, was simple. At the start of the match we should have staged an action and scored a goal.

Immediately after, the referee would have blown the final whistle of a match that was never played. Chile would have won and qualified for the World Cup. Everyone knows that under these conditions, the match will be won by default by Chile.

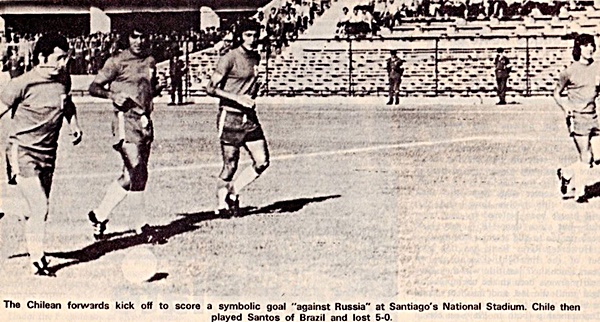

In reality, everyone thinks they know but still doesn’t know that on November 21, 1973 at the National Stadium in Santiago, Chile, a disgusting pantomime takes place. The Soviets forfeit and so we Chileans take to the field anyway.

How on the field? And against whom?

Here is another peak of arrogance reached by the men of the military junta. Chile must play the match alone. Yes, that’s right, on the field without an opponent. It’s something never seen before. A few moments before going on the pitch, the president of the Chilean federation came to the locker room and said to me:

“Francisco, you are the captain of the national team and you have to score the goal”.

I felt like my world was collapsing on me but I didn’t have the strength to refuse. I was becoming the key figure in a farce that would go around the world. I was becoming a symbol not only in sports but also in politics.

Yes, because that match was above all political. The Pinochet regime wanted to demonstrate its strength to the world which condemned its violence.

And I was chosen for a game bigger than me, Don Pablo.

A strange twist of fate, you understand?

The team has put on their costumes, boots and uniform of the national team. The ball is under the arm of the referee who has put on his black jacket. After all, cheaters do this in sports as in life.

They bring the ball from home and, if they can, the referee too.

And this referee, stepping onto the field, is endorsing on behalf of the International Federation not only Chile’s choice to play in the stadium of death and rape but also Chile’s absurd and yes, completely political idea of playing a match without opponents. Let’s not tell ourselves stories.

FIFA, sometimes, does politics. And how they do it?

Everything has to seem real. National anthem, played obviously by the military band, greeting to the crowd and then off. The ghost match begins.

Yes, because in this story, as in life, ghosts do not exist. Even if in this stadium there were indeed dead and from the floor of the locker rooms they have just swept away the blood. But here the ghost of a match that is not a match looms because Chile plays without opponents, against an empty goal.

And it is a match that will last only one action because if you play against no one, no one will put the ball back into play.

That Don Pablo Neruda laughed.

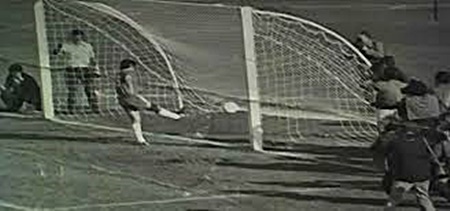

At that point the referee blew the whistle to start the match and I ran towards the goal. I don’t remember who passed me the ball.

Those ten or twenty seconds are completely erased from my memory. I scored without realizing it and immediately ran to the locker rooms amidst the din of the trumpets and the singing of the fans. I threw up.

Well the coach asked me if I was okay. I had to go back on the pitch because the Chilean federation, after the farce of my goal, had organized a friendly against Santos and the crowd was waiting.

The ghost match lasted ten touches of the ball. Ten touches between four Chilean players for the 17 most stupid and shameful seconds in the history of football. On the goal line of that Soviet Union that remained in the Soviet Union it is captain Francisco Valdés who hurls the ball into the net for 1-0 with a gesture that at the time might have seemed like strength but that, looking back at it today, seems full of anger and impotence.

The last pass before captain Francisco Valdés’ goal is by Carlos Kaslay. His family arrived in Chile from Hungary. You can recognize him immediately on the pitch not only because he sports an unlikely pair of black moustaches but because he looks like someone who spends his days on the assembly line. However, no one knows how to maneuver in the tight spaces of the penalty area like him. This is why everyone calls him that. He is the king of the square meter. But here there is no more room for maneuver if, like him, you sided with Unidad Popular and President Salvador Allende in the elections. One day, Carlos Kaslay would explain about the ghost match. When they told me what we should have done on the pitch I didn’t want to believe it.

I was already living badly knowing that many of my friends had been taken to that stadium and then tortured and killed. I felt like a coward. I was ashamed to continue my life as if nothing had happened. But you can imagine what kind of atmosphere there was in my country in those days.

You could touch the fear. You ran into it every time you moved, turned your head, raised an eyebrow. It took too much courage to defeat all that fear and I didn’t have all that courage.

Meanwhile, on the electronic scoreboard of the National Stadium of Chile the writing Chile 1, Soviet Union 0 appears.

A banner hangs above it. Youth and sports united here in Chile. Youth and sports united here in Chile today.

Now, Don Pablo Neruda, you may be wondering why you are writing to me?

What do I have to do with all this?

I told you before that this letter is a way to free my conscience from an unbearable weight. Let me explain.

When you died, on September 23, 1973, while Santiago was experiencing the most tragic moment in its history, I felt lost, bewildered, without a guide. I remember that I took a book from my library and I started reading one of your poems and I repeated it for hours and hours, until it became a part of me. That’s why I’m writing to you, Don Pablo Neruda.

Today, December 12, 1992, is the day that his body finally returned to Isla Negra, to his home, after years of exile in an anonymous cemetery.

Scoring that goal for me was a betrayal that I have never forgiven myself for. I leave this letter in front of your door, hoping to have paid the debt, but aware that the wound cannot be healed with words alone.

Así es la vida, that’s life.

With love and devotion, Francisco Valdez.

Here, the story is all here. Bitter and sweet like this confession letter attributed to the captain and goal scorer of Chile in the phantom match against the Soviet Union and which bore the name of Francisco Valdez. A letter that, in reality, Valdez never wrote, however, even if it is not authentic, this confession letter is still true and it tells us many things. The first is that day in November 1973, when the Chilean regime humiliated, in addition to the nation, also its own national team, by forcing it to play against a team that didn’t exist.

III

But above all he tells us about the enormous void left by Pablo Neruda, the only one capable of understanding and therefore forgiving those who did not have the strength to say no and who for many years fought with the ghosts no longer of the national stadium of Chile, but of his own conscience.

After all, Neruda was really a bit the father of Chile and a father, a true father, who knows how to accept and forgive the weaknesses of his children and we too, a bit like Don Pablo Neruda, must forgive those who couldn’t say no, like that Carlos Casley, who later explained that it took too much courage to defeat that fear and I didn’t have that courage.

Carlos Casley, who then took courage the day when, knowing that they would introduce him to Pinochet, showed up at the appointment with a red tie over his heart, leaving his hands in his pocket while the general and dictator held out his.

After all, a happy ending this time, is not easy to find because we are not in a fairy tale. Here there is no Peter Pan or Spider-Man who in an instant chase away ghosts and fears.

This is a story in which the bad guys win, at least at the beginning, because then yes, it will take 15 years, but Pinochet will go away, and this is an extraordinary and beautiful fact, will be driven out without violence, with the power of pencils, in a popular referendum. He had organized it to stay in power for who knows how long and instead it will be the most sensational of boomerangs, or rather, of own goals.

However, thinking about it, there is still another thing to tell, another own goal like the referendum, even if much smaller. One of those small and unpredictable things that ruin your party and your day, even if you’ve organized everything.

We love it when the cherry you put on the cream ruins your cake, it drives us crazy when you go to the parade in the white uniform and the first passing pigeon mistakes you for a monument and leaves on your shoulder what everyone thinks of you.

And then you should know that in the stands of the ghost match against the Soviet Union there are 20,000 people who cannot be sent home with many greetings and thanks. Also because there is a qualification for the World Cup to celebrate.

For this reason, after the ghost match on the pitch of the National Stadium of Chile, the most important and admired club of the moment takes to the field.

For 30,000 dollars, obviously American, Pinochet has signed Santos, Pelé’s Brazilian team, the strongest player in the world. Just enough time to go back to the locker room, erase the name of CCCP from the electronic scoreboard and insert that of the Brazilians that Chile and Santos face each other in a friendly match, but this time at least a real one.

These are the line-ups:

Chile with Olivares in goal, then Maciuca, Figueroa, Quintano, Arias, Rodríguez, Valdés, Reynoso, Kasley, Ahumada, Crisosto,

Santos responds with Secas between the posts, Hermes, Marinho, Pérez, Vicente, Roberto, Alberto Torres, Leo Oliveira, Masigno, Eusebio, Nenè, Edu.

Something doesn’t add up though. Excuse me, but where is the first man?

They hired Santos because he plays there, Pelé, so why are there Masigno, Eusebio, Nenè and Edu in attack?

Did they leave him out?

Come on, Orei, he always sits on the throne, not on the bench.

Pelé is not there though.

Fantasized like the Soviet Union. We do not know and will never know if this absence is a response to the Chilean regime and its violence, or if Pelé is injured or if he simply did not feel like getting on the plane. Of course, thinking that Pelé could have sided against the established power, well, it is not probable.

Maradona will do these things in about fifteen years.

However, if we have to choose, we like to think that Pelé’s ghost is also the protest for what happened in Chile.

Also because it must be said that Pelé’s teammates do not take the match lightly. But what a friendly, in what is the stadium of murders, the Santos players play the match to the death. For Chile the friendly will be hell.

In 13 minutes, between the 26th and 36th of the first half, Santos scores four times. Nenè, Edu, Eusebio and Nenè again.

In the second half then another goal by Edu.

5 – 0!

The party, just begun, is already over.

And many greetings to Kissinger, Nixon and General Augusto Pinochet!!!

Today the national stadium of Chile is no longer what it was then.

Today it is a facility in step with the times. However, a small, very small portion of the north stand has been left intact as it appeared in that September of 1973.

No one has the right to sit there during the games, because that is a warning to anyone who enters that stadium today.

Here a sign reports these few words.

A town without memory is a town without future.

Translated from italian language by Pjerin Bj.

30 August – 20 September 2024

Source of the original material: © RadioRaiUno | Torture, fughe e vendette – Germania 1974 – “La partita fantasma e i fantasmi di Santiago del Chile” by italian giornalist Francesco Graziani

Photos are courtesy of Google!

__________________

Sports Vision+ / The Hour of Champions in activity since 2012

Discover more from Sports Vision +

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.