100 of these years to British Football | “Home Championships”, Clubs in Europe, “The Premiere League”…

A journey through British football with its century-old teams. From Man Utd to Tottenham, from West Ham Untd to Wolves, from Hibernian to Glasgow Rangers. A movement that has made the history of this sport and that continues to do so with its coat of arms and great charisma.

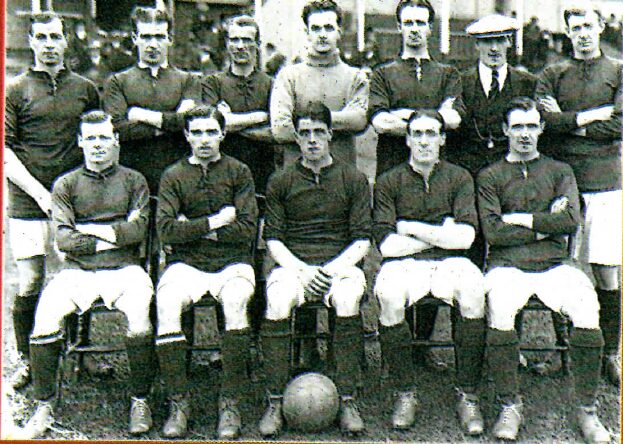

Liverpool of the 1914 beaten by Burnley in the FA Cup final

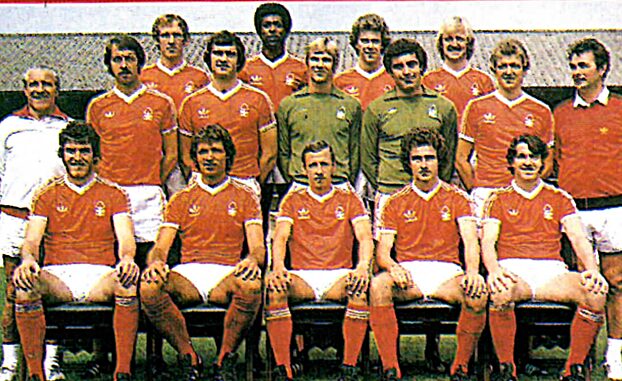

Nottingham Forest of the 1977-1978 season , winner of the second league title!

1.

The reference to national teams and the impact they have had on the spread of football in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland is not an aspect to be underestimated, even if the Anglo-Saxon sporting culture has always favored club competitions, those in which the everyday feelings of ordinary people come into play, in which interest in national teams is only occasionally awakened.

However, some representative competitions, given the illustrious stages and international prominence, have gone down in history.

And if for Ireland, Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland we will mention individual matches that have produced memorable memories, without causing epochal changes or favoring the birth of new champions, for England some circumstances have truly marked an era.

It is known that for the first few decades, given the backward development of football outside the United Kingdom, at national level the most frequent clashes were between teams from the island, and it is no coincidence that one of the longest-lasting events, unfortunately killed by the growth of international commitments, was the so-called “Home Championships”, the series of matches, with a round robin, between Scotland, England, Ireland, Wales and Northern Ireland, abolished in 1985 when it seemed to many that this internal slaughter was holding back the comparison with other nations (moreover, more and more players were finding excuses of all kinds for not accepting the call-up).

For decades, the Home Championships had represented a very important end-of-season event, characterized among other things by the challenge between the English and the Scots, on alternate grounds every year.

Scotsman Eddie Gary, a pillar of Leeds in the 70s!

It was on one of these occasions, precisely in 1977 saw the infamous pitch invasion at Wembley by the victorious Scots (2-1), who even uprooted the goal posts and roamed across the sacred turf, turning half of London upside down.

But the match that many remember, in the early part of the history of British football, is perhaps the one from 25 November 1953, when Puskas’ famous Hungary took to Wembley, who twelve months later would challenge West Germany for the world title in the World Cup in Switzerland, losing 3-2 in the final.

The English, who for decades had refused to mingle with the masses of other nations, declining invitations to every World Cup until 1950, had already suffered a huge shock in their first World Cup, when they were defeated 1-0 by the United States.

The shock of that afternoon at Wembley, however, was stronger than that of a defeat in a distant land, a demonstration that was not very exciting in the homeland; Hungary walked away winning 6-3 and leaving on the pitch the ruins of a team and a movement that had realized they were no longer superior to the world.

Yet in that English eleven, coached by Walter Winterbottom, the best of the island’s football played, Billy Wright, Stanley Matthews, Stan Mortensen.

And the same men, a few months later, on 23 May 1954, were humiliated 7-1 in the “return” match, marking the definitive demise of the English sense of superiority.

For Scotland there are no particular triumphs, except moments against England, but on the contrary the National team has always assumed a characteristic so pleasant as to be almost hateful; that of arriving very close to the great goals, but always failing them by a hair’s breadth and giving in against inferior opponents.

In the 1974 World Cup, Scotland beat Zaire only 2-0, and draws with Brazil and Yugoslavia were not enough; in 1978, after qualifying in the dramatic play-off in Liverpool against Wales, won 2-0, the Scots collapsed 3-1 against Peru, despite the initial advantage, then barely equalized (a comical own goal by Eskandarian) against Iran, finally dominated Holland, going ahead 3-1 (an extraordinary goal by Gemmill), then just one goal away from qualifying, before conceding the 2-3; in 1982, once again eliminated due to goal difference against the USSR; in 1990, qualification for the second round narrowly missed, when the Brazilian Muller gave his team 1-0 lead eight minutes from time (but the initial defeat against Costa Rica had been disastrous); and in 1998, in the match against Morocco that could have meant progressing to the next round, yet another collapse, 0-3.

For Northern Ireland, the pinnacle of success at national team level came on two different occasions: the great adventure at the 1958 World Cup in Sweden, which ended only in the quarter-finals against France, with top scorer J. Fontaine, but especially in the 1982 World Cup, when the Greens, coached by Billy Bingham, won their group, beating the hosts Spain 1-0 in Valencia, with a goal by Gerry Armstrong, an episode so famous that a newspaper dedicated to the team’s fortunes is still titled “Arconada…Armstrong”, to replicate the commentator’s cry when the Spanish goalkeeper failed to hold on to the cross from the byline which Armstrong, in fact, sent into the goal.

For Ireland, the national team meant Jack Charlton, the (English…) manager who led the team to very good performances in the 1988 European Championships (with a victory over England), in the 1990 World Cup (defeated against Italy in the quarter-finals, 1-0), in the 1994 World Cup (knocked out by Holland in the second round), while the subsequent events were not so happy, after the farewell of Big Jack and his cheerful sessions in… the beer hall.

Less illustrious is the CV of Wales, whose best result was the quarterfinals of the 1958 World Cup, with a narrow defeat (1-0) against Brazil, with a goal by Pele.

2 – The “maximum wage”!

All these events involving national teams would have had a very different impact if an almost decisive event had not occurred in 1960, namely the abolition of what in English is called the “maximum wage”.

It was a turning point, desired by a group of athletes led by Jimmy Hill, one of the most prominent figures in English football, later president of Coventry City and then Fulham, and a successful television commentator, although not always much loved. Jimmy “The Chin” (due to the enormous size of that part of his body, wisely covered by a permanent goatee) fought for years and achieved the result of liberalizing salaries.

From that moment on, in fact, footballers, who for some time could be transferred from one club to another and were professionals, but equated (salaries in black and benefits aside) to “normal” workers, will begin to rise to a higher salary level: if the football heroes of the first decades had been ordinary people, and proud of being such, like Stanley Matthews who often claimed to feel lucky to earn money by playing his favorite sport, now the lifestyle of some of them, the earnings and the consequent popularity created the “character” of the footballer, a clear detachment from the previous situation.

Furthermore, the arrival of television, albeit on a smaller scale than now, and the awarding of the 1966 World Cup to England, constituted another very strong push towards the growth of the football movement, coupled with a better organization of the club; traditionally owned by individual benefactors or small entrepreneurs who had run them like family shops, they now became more professional associations, and powerhouses such as Liverpool, Manchester United, Arsenal were born.

February 7, 1958: The Manchester tragedy takes place in Munich

For the smaller British nations, the growth of the major English clubs meant a greater emigration to the stronger league, and it was in fact during this period that the hemorrhage of athletes from Scotland, Ireland and Wales to England took on unprecedented proportions.

Meanwhile, international commitments were also growing; an important moment of this era was the 1960 European Cup final between Real Madrid and Eintracht Frankfurt: 135,000 spectators flocked to Hampden Park in Glasgow, few of whom were supporters of the two competing teams.

Bill Shankly, legendary Liverpool manager, with the FA Cup in 1974

They were almost all Scots and English, attracted by the name of the great Real, who gave a stunning show by winning 7-3. Many believe that that night paved the way for the committed involvement of English clubs in the cups, even though in 1960 Birbingham City had reached the final of the Fairs Cup (later the UEFA Cup), losing against Barcelona.

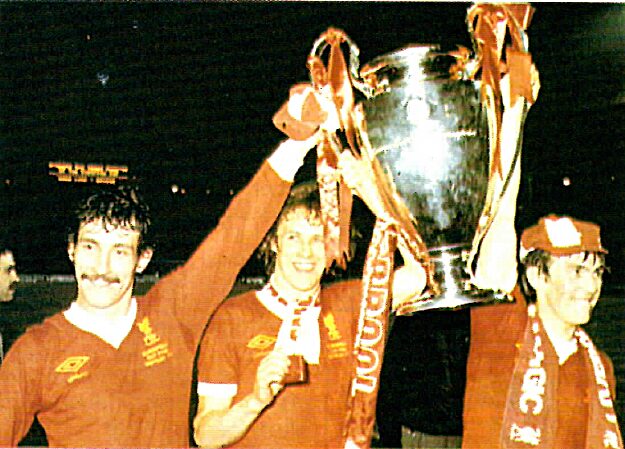

Once launched into the European arena, British clubs gradually put together a good series of performances: in the Cup Winners’ Cup, the 1960s brought a triumph to Tottenham Hotspur, West Ham, Manchester City, the European Cup to Celtic in 1967, to Manchester United of George Best and Bobby Charlton in 1968, and even in the 1960s this success continued, with the extraordinary series of seven European Cups in eight years, between 1977 and 1984.

Denis Law of Manchester United

The Premier League In the mid-1980s, the growing problem of hooliganism among English supporters was addressed by the Taylor Report, which had taken into account, in addition to the “Heysel” tragedy, also the one in Bradford in May 1985 (53 deaths in the fire in the central stand): the seats created fewer opportunities for potential hooligans to congregate, as they were not certain of sitting together, and the security measures also encouraged those who until then had kept far away from stadiums, such as members of the bourgeoisie who abhorred brutality, to timidly appear in the facilities, which had been modified, often with very heavy aid from the Football Trust, a sort of football credit, and were more comfortable.

With great seriousness and effectiveness, the most dangerous exponents of residual hooliganism were reported, unmasked and limited, and the situation changed even more radically in 1992, with the revolutionary creation of the Premier League, the elite league which came under the jurisdiction no longer of the Football League, but of a separate branch of the Football Association.

The huge television deal signed with BSB for the sale of match rights brought Premier League teams unprecedented sums of money: with it, the clubs completed the modernization of their stadiums or strengthened their squads, often by purchasing foreign players.

The other side of the coin of all this is the progressive change in the public; convinced also by the works of writers such as Nick Hornby, many members of the bourgeoisie and the middle classes have approached football, finding an enthusiastic welcome from the clubs which have consequently created even more aseptic and hospitable environments, increasing the prices of the tickets to the point of making any match difficult to access for those who do not have a minimum economic availability.

Chloroformed by comfort and fashion, the world of traditional fans had already found a way to express itself for years, with the birth of the so-called fanzines, a cultural phenomenon that has had great importance in spreading a non-violent message.

Kevin Keegan, the star player of Liverpool and England National Team

Through these magazines, created, produced and conceived by fans for fans, information was made available to the public that differed from the official pamphlet of the “programs”, the official magazines sold at matches, and a real movement was created, often of passionate resistance, often of cautious support for innovations, but with great attention and caution towards the ever-increasing number of characters who, coming from nowhere, rose to the management of the clubs, risking dragging them away from their cultural and popular roots.

3 – Media Football

In England, to experience atmospheres like those of the past you have to go down to the level of the First Division or even lower, while the Premier League, while retaining peculiarly English characteristics, has become watered down in terms of purity: the game is certainly less exciting than in the past, as far as pure entertainment is concerned, and the greater diffusion of football also in the media, multiplied in number, has created a sort of continuous scrutiny on clubs and athletes, still lower than what happens in Spain or Italy, but incredibly higher than what happened until a few years ago, when football was written about in a dry manner in the newspapers, in childish tones in children’s magazines like “Shoot” or “Match”, and television broadcasting was limited to the hour of highlights on Saturday evening, in Match of the Day, on the BBC, and a live broadcast on the private channel ITV.

In other countries, however, the growth of the Premier League has led to a greater flight of talent towards the easy money of the league and an impoverishment of the clubs in relation to the English ones: declining audiences, attempts at reorganization on a national basis (see the Welsh championship snubbed by the major clubs) willingness to join forces with other countries with similar characteristics as “Rangers” (an almost solitary power) and Celtic would like to do in Scotland by joining forces in a Nordic championship with Dutch and Scandinavian clubs.

Queen Elizabeth gives to Yeats of Liverpool the FA Cup in 1965

As the third century of football begins in the British Isles, there is greater wealth, less hope, less equality, and the Notts County fan feels almost like a fool in his affection for his little team, while around him dance boys and girls who may not even know where “Old Trafford” is, but wear the shirts of Manchester United, happy to have seen their club give up the FA Cup, to play in the insipid little World Cup for clubs in Brazil.

Manchester United Team in 1968 with the Champions Cup just won

Amen!

References: “Calcio 2000” N. 33 Agosto 2000 (Italian magazine); “100 di questi anni” by Francesco Caremani e Roberto Gota, pages 141-143.

Translated to english by: Pjerin Bj.

New York 18, 2025

________________

Sports Vision+ Plus / Champions Hour in activity since 2013

Discover more from Sports Vision +

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.